Vince Gomez: “Music education is not just music, it’s social justice.”

by Alex Walsh

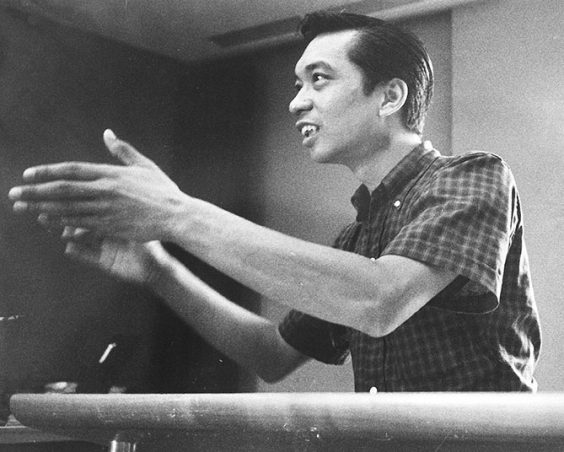

Vince Gomez

Vince Gomez is a violinist, bassist, conductor, music educator, native San Franciscan, Local 6 Life Member, and a proud American Filipino. Like many of his generation, he broke down racial barriers. Now in his 80s, he continues to mentor music teachers and hustle for gigs as much as he can.

Vincent Gomez was born in San Francisco General Hospital on February 2, 1935 (Groundhog Day). His parents were Filipino immigrants. As a child his family lived in a hotel on the Embarcadero directly across from Pier 3, near the Ferry Building. “As a kid, the Embarcadero was my playground. In our hotel we had 4 rooms that were connected to make a 3 bedroom apartment. We shared the bathroom in the hall with other people. There was a produce market on Drumm St. and to the left of the hotel were Wellman Coffee and Planters Peanuts. This was an industrial area with lots of hobos and drunkards, and was considered a slum. Today it’s a tennis court and swimming pool next to the Hyatt Regency.”

Vince’s father worked as a cook and steward for the Coast Guard, which was based in Alameda. He had migrated to Seattle as a young man and eventually settled in San Francisco at the old International Hotel on Kearny St. in what used to be called Manila Town. Vince’s mother migrated to Honolulu to work as a Sakada sugar cane worker in 1923. She came to California where she worked in the fields in Salinas and then in San Francisco as a hotel maid. When she became pregnant she stopped working and stayed home to raise Vince.

Vince was an only child. When he was five years old his Godfather recommended he take music lessons. “Somebody said I picked up two coat hangers and mimicked a violin and bow, so my Godfather said, ‘Give him a violin, he needs discipline. If you don’t give him some discipline he’s going to be a trouble maker.’ My Godfather pushed it because he knew how important music was for the people of the Philipines. My folks sacrificed for me. My father made $50 a month in the Coast Guard. $16 went to the hotel, $16 went to music lessons, and we lived on $18 a month.”

Growing up in North Beach, Vince played and went to school with Irish, Italian, Chinese, and Black kids. “If you saw a white kid or a black kid their race was very clear. But they used to ask me, ‘How come a Chinaman like you has a Mexican last name? They didn’t know what a Filipino was.”

Vince at 9

Vince continued with his violin lessons and in 7th grade received a positive write-up in the neighborhood paper for one of his recitals. “I found that music gave me an edge in school. I wasn’t just a student–I could play the violin!” Vince also loved basketball and played on different teams in recreation and church leagues and eventually at Galileo High School where he became friends with soon to be megastar Johnny Mathis.

In his senior year, Vince’s music teacher, Mr. Kenneth Ball, offered to take him to audition at the College of the Pacific (now UOP) in Stockton, CA. Vince was offered a half scholarship which paid for his tuition and books. He covered his room and board by joining a fraternity and working in the kitchen.

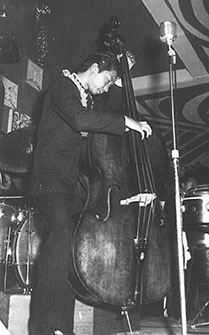

In college, Vince excelled in both music and sports, but by his third year realized he had to focus exclusively on music. He started playing jazz bass in addition to his violin and viola studies, and joined the school big band. “Jazz at that time was not taken seriously by the school. It was looked down on. They made the big band rehearse in the school radio station rather than the conservatory rehearsal hall.” When Dave Brubeck, a former student, played a concert at the school in 1953, it was the first time they let a non-classical musician play the school’s Bosendorfer piano. “Today they have the Brubeck Institute at the UOP, which is a big deal. They even named the street near the conservatory Dave Brubeck Street. Jazz used to be a no-no. Now all the colleges have jazz programs.”

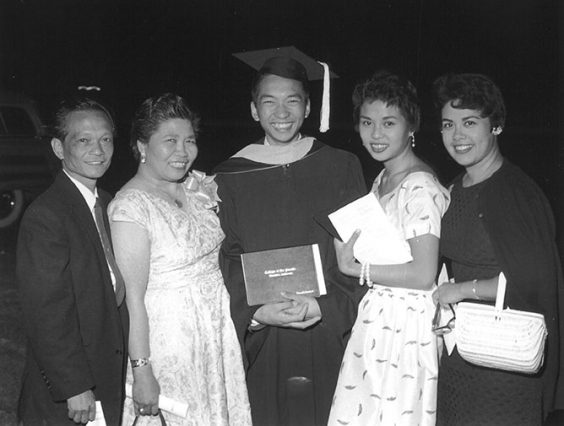

From left: Vince’s father and mother, Vince, his first wife and her friend

In his second year of college Vince began dating Cornelia Bocar, a senior at Washington High School in San Francisco. She was also a musician and played piano for Johnny Mathis at school assemblies. After high school she went to SF State and then transferred to UOP where the young couple learned they were going to have a baby. When they heard the news they drove to Nevada in the middle of the night to get married, telling everyone they’d been married for months to avoid embarrassment.

Vince’s fraternity did not allow black members, but his draft card said he was white. This did not stop him from experiencing discrimination when he was denied housing. “We were going to pay and pick up the key and the landlord said, ’Oh, Mr. Gomez, we can’t rent to you because there’s a clause in our covenant that says no non-Caucasians can live here.”

Vince did not know why he was classified as white on his ID card. “The draft card I had when I turned 18 (in 1953) indicated that I was white. I never knew how they came up with that label at that time. It seemed that they had only two choices, white or black, on the card. I never knew if that was the common label for ‘OTHERS’”.

Vince graduated from college in 1956. He tried to find work in the Stockton area as a music teacher but had no luck. His friend Clark Burroughs, the lead singer in the jazz vocal group the Hi-Lo’s, suggested he try Los Angeles.

“My first teaching job was in Lowell Joint school district between LA and Orange County on Highway 39. In those days there were no homes, just orange groves.” Vince covered all the classrooms for the entire district, K-8, where he would bring in an autoharp and lead the kids in singing. “If they were studying about the Erie Canal their books included a song about the Erie Canal, so we tied in social studies with music. In those days a teacher like me was happening. Today you don’t have kids singing anymore. There’s no one going into the classroom. And if the teacher doesn’t sing or doesn’t like music, they just do the three R’s–reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmatic.”

“One time my teacher threw me into a gig subbing for him with all these heavy studio cats. It was in Db and I didn’t know Db—I realized I had to go back to woodshedding.”

Vince freelanced as much as he could in local orchestras, and continued to study the bass. He found a teacher, Ralph Pena, a studio pro who had played with Frank Sinatra and George Shearing. “He was my mentor. He took a chance on me and borrowed money from the Local 47 Musicians Credit Union so I could get a bass. I paid it back, $17 a month for 12 months. It’s the one I use today. Ralph Pena really helped me become a bass player.”

“One of my biggest gigs was playing for the Hi-Lo’s at the old Shrine auditorium in LA. It was called ‘A Jazz A La Carte.’ The bill included the Oscar Peterson Trio, Shorty Rogers Big Band, and Sarah Vaughn. I could read charts. Having been trained to read, I came from the other direction where I had to learn to improvise.”

School teachers were not paid during the summer months, so Vince decided to try his luck in Las Vegas. “The summer of ’57 I had no money coming in, so we went to Vegas with Clark Burroughs’s wife who was a dancer. We drove in a Morris Minor convertible in the evening when it was cooler. A musician saw us coming into town with the bass sticking out and yelled, ‘Hey, there’s a new bass player in town!’”

By the end of the summer things were going so well that Vince decided to stay. “I told the school district I was going to stay working as a musician. I was only 22. It was glamorous! I was around all these famous people. I was in show business now–it was happening!”

“My first big gig in Vegas was with Jackie Cain and Roy Kral at the Thunderbird Hotel. Other gigs included playing with Dinah Shore, Victor Borge, the Paris Sisters, and comedian Shecky Greene. I played violin with Dinah Shore. It was a week at the Flamingo Hotel. You didn’t get a steady gig for four months, it was a week here, two weeks there, depending on what stars were in town. I worked with the Paris Sisters at the Riviera Hotel where I hired a great trombonist named Carl Fontana. He’s well known among jazz musicians.”

A year later, Vince and his wife divorced. Heart-broken, he returned to Los Angeles. “I asked my parents in San Francisco to take care of my kid because I was trying to get established back in LA. I found a teaching gig in Watts, in an all-black neighborhood. At night I played in a group called the Paul Togawa Afro-Jazz Orientals in a Mexican nightclub in East LA.”

During Christmas vacation in 1959 Vince visited San Francisco where he worked a few gigs in Chinatown with his college buddy Mike Montano. Because his ID said he was white, Vincent was given the choice of joining the white Local 6 or the black Local 669. “I couldn’t understand when they said black union or white union. In San Francisco? I didn’t know there was a problem with race. Growing up I had been accepted in school. The Union wasn’t like that in LA.”

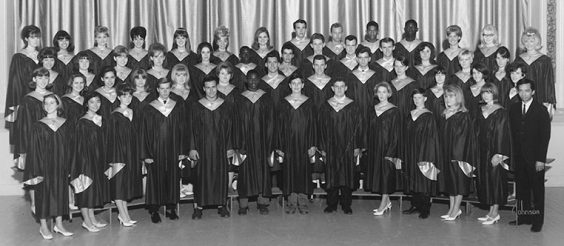

Acappella Choir, Tracy, CA, 1966

Vince returned to SoCal for another year and then decided to move back to San Francisco. By this time Local 6 and 669 had merged. He joined Local 6 and soon established himself in the club scene. “When I got my union card in San Francisco it was to play the clubs in the Chinatown area which are now all gone—The Rickshaw, Mr. Lucky, Dragon Lady—I was the singing MC at the Chinese Sky Room where my stage name was Vince Gee.”

“I remember driving through Texas in the early 60s and I went to the union office and said, ’I’m a musician and my car broke down here in Amarillo, do you think I could get a job? A job for a bass player or something? They said we have a black union and a white union. My I.D. said I was white but I didn’t look white so I would have to choose. They had the same problem as Local 6. They wouldn’t let the musicians play together.”

Vince found a teaching job at Benjamin Franklin Junior High in the Fillmore district where he taught for two years from 1960-62. “I took a group of kids to a chorus festival where previously they had never gotten a good score. They got a superior rating—for the first time ever. My first day teaching there a 14-year old girl said, ‘You can stay, we like you.’”

“See, you get past the skin thing and these kids are just like everybody else, they want to sound good, they want people to believe in them.”

In 1962 Vince applied for a fellowship at the East West Center of the University of Hawaii (UoH) to study ethnomusicology. Unfortunately, there was a mix-up in his application. The school thought he had a low grade point average because UOP graded on a 3.0 system and UoH graded on a 4.0 system, so he did not get accepted. “I’d made the decision to follow through and go to grad school anyway so instead of ethnomusicology I went into music education. It turned out to be the right decision. My interests then developed into getting people to understand that ALL cultures have music, because I wasn’t taught that—I was a classical musician. I played Beethoven, Bach, and Brahms. Music teachers at my time were taught to teach western music. Jazz opened me up to different things, and being more of a philosopher, I thought music education would be more fun than studying Koto in Japan or Gamelans in Indonesia.”

Vince and his wife Carol in 1990. They met in 1976 when she hired him to be the Music Director for Berkeley City Camps

Vince spent his days playing in chamber groups, learning how to teach choral music, bands and orchestras, and his nights playing bass in jazz clubs and violin in the Honolulu Symphony which included performances under guest conductors Arthur Fiedler and Andre Kostelanetz. He tried to substitute for the music teacher at a local private high school but the school said no because he was Filipino. “There was a stigma against Filipinos in Hawaii. They were only seen as field workers.”

After graduate school Vince returned to the same district where he he began teaching. During this time he began working as a music director for the National Conference of Christians and Jews. “Every summer they held a week-long summer camp called Brotherhood USA which brought together kids of all different races and religions from the LA area. One of my students who I’ve kept in touch with over the years, Dr. Arthur Cribbs, attended the camp and is now the minister of the Filipino American United Church of Christ in LA. His congregation’s Filipino, and he’s black! They love him.”

In 1965 Vince moved to Tracy, CA where he taught high school for five years and then back to the Bay Area where he taught in San Carlos, Berkeley, and part-time at UC Davis. In 1974, Vince was hired fulltime at Cabrillo College in Aptos, CA. “I didn’t want to leave Berkeley High. They were some of the best musicians I ever worked with at that level, but the pay was better at the community college, and the schedule was less hectic.”

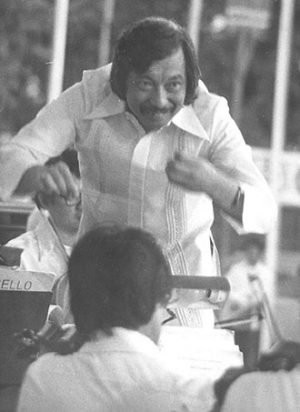

Conducting in the Phillipines, 1981

At Cabrillo, Vince became involved in the National Association of Music Educators where he served as the chairman of the multi-cultural music commission. “They used to call all the other music ‘non-western music’. The word ‘non’ meant they’re not people and that good music was only European music. We tried to change that.”

In 1980, Vince took a sabbatical from Cabrillo to work on a research project. “My project was to go to the Philippines and other Asian countries to see why they played western music. The answer? The European influence. I ended up staying in the Philippines the entire time. I got involved with the Manila Symphony. When my year ended I was asked to stay and develop a symphony in Cebu, the island where my mother’s family came from. They said, ‘Develop the Cebu Symphony and when you’re ready to do a concert we’ll send you some Manila musicians.’ I stayed for another year. They ended up paying me in pesos rather than dollars, so I didn’t make as much as I thought I would.”

In 1984, Vince competed and was selected for a year-long Fulbright Lectureship in Ecuador. Four years later he won a Fulbright Lectureship in Honduras. “Cabrillo didn’t mind me going, it made them look good to be able to say they had teachers involved in the Fulbright program.”

In 1990, at age 55, Vince retired from Cabrillo to focus on mentoring teachers in the classroom. Since 1993 he has been an Artist in Residence at the San Jose Unified School District.

Throughout the 80s and 90s, along with playing many casuals, Vince conducted the Santa Cruz Youth Symphony and Monterey Youth Orchestra. During the 1990s and 2000s, he played weekly gigs at the Washington Square Bar & Grill (the Washbag) in North Beach with Dick Fregulia and performed as the Vince Gomez Trio in Stinson Beach.

Today, at 81, Vince continues to play and teach as much as he can. “I’m scheduled to go to George Fox University in Oregon to help with their music education program. I get to help teachers before they go out into the field. How do you reach kids that walk in and say, ‘I don’t like music, I don’t care about music’—the kids who don’t want to be taught? I believe if we had better teachers with those hard to reach kids than they would turn out as good people in society. It’s always hard because you’re fighting through the problems of society in order to teach your subject.”

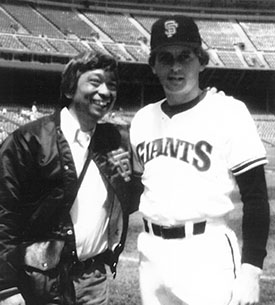

With Duane Kuiper in 1978

Vince Gomez On Being A Ball Dude

I’ve been a season ticket holder with Giants since 1978, and I became a Ball Dude in 2000. The owner, Peter Magowan, sat right next to me at the ballpark and I got to know him pretty well. One day he asked if I’d like to be in the Giants Community Fund, which entails a couple meetings during the year where we vote on grants for non-profits. The director, Sue Petersen, asked if I’d like to be a Ball Dude. I said, ‘Yeah, I’d like to be a Ball Dude!’

I’ve been a season ticket holder with Giants since 1978, and I became a Ball Dude in 2000. The owner, Peter Magowan, sat right next to me at the ballpark and I got to know him pretty well. One day he asked if I’d like to be in the Giants Community Fund, which entails a couple meetings during the year where we vote on grants for non-profits. The director, Sue Petersen, asked if I’d like to be a Ball Dude. I said, ‘Yeah, I’d like to be a Ball Dude!’

Many people pay to do it. Their company donates $10,000 so they can be a Ball Dude and go to Ball Dude Camp.”

My first game I was looking for my Godson to give him the ball, so I was walking away from my seat. Everybody said, ‘Vince, you’ve got to get back, you’re holding up the game!’ I didn’t know it was wrong to go looking for him.

Krukow and Kuiper know me—they were players when I met them. Now they’re the announcers. They see me on the field and they say, ‘Hey, there’s Vince, he’s one of our favorite Ball Dudes. He’s a great musician.’

I’m a talkative guy. I like to talk to the fans. There were times when Krukow and Kuiper would say, ‘Yeah, Vince is running for Mayor, that’s why he’s talking to everybody.

I do it a couple times a year. Sometimes they have Filipino night and they call me. After the game on Sunday I had 90 people mentioning on Facebook that they saw me. That shows how powerful TV is. More people know me now as a Ball Dude rather than as a musician!

“Filipinos are one of the largest minority populations in the US. I am a composite of those immigrants that came in the 1920s and 30s–I’m a result of that generation. They call us The Bridge Generation.”

Vince would like to recognize the following Local 6 members that were his former students:

Berkeley High School: Shinji Eshima, Doris Fukawa, Robin Hansen, Steve Henry, Jonathan Knight, Carla Picchi

Cabrillo College: Holly Heilig-Gaul, Stan Poplin

SCYO / MYO: Leslie Chin, Michelle Maruyama, Henry Viets, Nicole Welch