STUART CANIN: “…An Excellent Violinist.” — Harry Truman

by Alex Walsh

During his career, Stuart Canin has served as the concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony, Los Angeles Opera, and major Hollywood studios. A graduate of Juilliard, he won the Paganini International Violin Competition, taught at Oberlin, the University of Iowa, the San Francisco Conservatory, and was a founding member of the New Century Chamber Orchestra.

During his career, Stuart Canin has served as the concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony, Los Angeles Opera, and major Hollywood studios. A graduate of Juilliard, he won the Paganini International Violin Competition, taught at Oberlin, the University of Iowa, the San Francisco Conservatory, and was a founding member of the New Century Chamber Orchestra.

“The most nervous I ever was, was playing for Truman, Stalin, and Churchill. I was only 19 years old! I still remember seeing these three gentlemen in the room, with no one else around.”

Stuart was drafted into the Army as a rifleman in 1944, just as he was about to go to Juilliard. He was sent to Europe, but fortunately, he did not see any action because the war there was coming to a quick end. With fighting over, the Army took a look at Stuart’s record and sent him to Paris to help form a G.I. orchestra. “I entered what was called a soldier’s show company. People like Mickey Rooney were in it; all kinds of wonderful people were brought together to entertain the troops.”

Soon after President Roosevelt’s death, Stuart’s commanding officer got the message that President Truman was coming to Potsdam, Germany. He thought the President, a classically trained pianist, might like some music. Mickey Rooney went along, but didn’t get to perform because they didn’t realize Stalin would be there and wouldn’t appreciate Mickey’s humor.

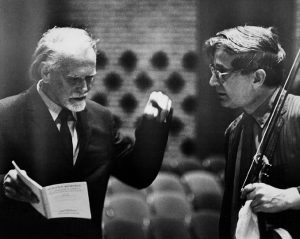

Stuart and Eugene List rehearsing for their performance for Truman,

Churchill, and Stalin at the Potsdam Conference, Germany, 1945.

“So that famous day—July 17, 1945, at 6:30 in the evening—we were standing on the upstairs porch. Down the street came one limousine after another. And out of one steps Stalin, then came Churchill, then Truman. After dinner, they came out onto the porch where there was one sofa for three people. Truman sat in the middle, Stalin on his left, befitting his political affiliation, and Churchill on the right. Eugene List, the pianist, and I, were a little duo team. Truman said, ‘Gentlemen, play something.’ So we played, having no idea it was going to be history.”

Their performance turned out to be international news. It was one thing the media could write about that wasn’t controversial. The conference lasted three more days, and Truman asked the duo to stay and play for the American generals. He later sent Stuart an autographed picture of himself: “Best wishes to an excellent violinist, Private First Class, Stuart Canin – Harry Truman.”

Back in Paris, the G.I orchestra was finally formed, and then stationed in Frankfurt, Germany, where they gave concerts for British, French, and American troops. “We traveled around the occupied territories, playing concerts,” recalls Stuart, “It was a really fantastic experience. I played solos many times with the orchestra. It was the beginning of my professional life.” Stuart came home in August 1946, after 22 months, and went to Juilliard on the GI Bill.

FAR ROCKAWAY

Stuart was born in 1926 in New York City. His younger brother, Martin, was born four years later. Stuart’s father, Monroe Canin, was a cigar salesman, and one of the founders of the Tobacco and Warehouse Union in New York. His mother, Mary, stayed home to raise their two sons. They lived in Far Rockaway, a mostly Jewish community. “Rockaway Beach was the rich part, and Far Rockaway was the poor part. It was basically a summer community, with a lot of bungalows on the beach. We lived there all year, a block away from the ocean.” From June to Labor Day, the bungalows were rented by families who came from Manhattan and the Bronx. The men would commute to work during the week while their wives and families vacationed.

The Canins took a great interest in their children’s musical development. Stuart’s mother was a self-taught pianist, and his father loved the violin. “My father was a violin nut. He was a terrible violinist, but he adored the violin. In 1931, he brought home a little fiddle and said, ‘Let’s try this.’” His father would practice with him for an hour every morning before work. At night, Stuart would play with him, and for him. Stuart’s brother, Martin, would later become a piano professor at Juilliard.

On December 30, 1936, Stuart performed François Schubert’s “The Bee” on an episode of the Fred Allen radio show. This started the hilarious Jack Benny/Fred Allen radio feud, in which Fred Allen proved a ten year old could play better than Jack Benny. The feud went on for four years, culminating in a movie called Love Thy Neighbor. During the movie premiere at the Paramount Theater in New York City, Jack and Fred presented Stuart with a check for $1000 to further his music education. Twenty years later, in a Where Are They Now? episode, Stuart was flown out to Hollywood to appear on the Jack Benny television show, again proving he could play better than Benny.

In school, Stuart’s teachers recognized his talent and excused him from orchestra and gym so he could practice. He began studying with the renowned teacher, Ivan Galamian, whose students included Itzhak Perlman, and Pinchas Zukerman, at the Henry Street Settlement in Manhattan, a school established for underprivileged kids to study music. For his safety, and because this was during The Depression, Stuart’s mother always went with him on the Long Island Railway, claiming that he was under twelve so he didn’t have to pay full fare. That went on for several years.

JUILLIARD

Upon his acceptance to Juilliard, the Canin family moved to the Bronx, just a few blocks from Yankee Stadium, so Stuart could have an easier commute to school. He turned 18 in April 1944, and by October was drafted into the army. “I brought along a cheap violin. When I was boarding the troop ship in New York harbor, my commanding officer asked, ‘What’s that for?’ I told him, ‘You never know.’”

Upon his release in 1946, Stuart started at Juilliard, where he continued to study with his teacher, Mr. Galamian. He met his future wife, Virginia, at a Saturday night string quartet party. They married a few years later, and eventually had two sons. Upon graduation, Stuart found work playing in the New York television studios and subbing for various orchestras. When Mr. Galamian encouraged him to take a teaching position at the University of Iowa, he went for it. “I enjoyed it. I had a lot of time. I was able to practice, to read, and to study music. In New York I was always at the beck and call of a contractor who wanted me to come for a date. I just didn’t like it. I just didn’t think that that was what I had trained for.”

The Canins stayed in Iowa for eight years. During this time, Stuart received a Fulbright Professorship to teach for a year in Freiberg, Germany. The young couple had a wonderful time traveling while Stuart played concerts and taught at neighboring universities. They returned to Iowa and had their first son, Aram, in 1958.

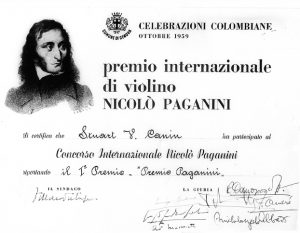

Stuart won the Paganini Award in 1959.

THE PAGANINI COMPETITION

In October of 1959, Stuart beat out 25 finalists to win the Paganini Violin Competition in Genoa, Italy. “The famous violinist, Zino Francescatti, said that would be a good competition to go for. Every competition has a different repertoire, and I knew this repertoire. I could play Paganini’s music very well.” The Italian President presented him with the award, and he was allowed to play on Paganini’s violin. Winning the Paganini award brought international attention to Stuart, and many opportunities to perform as a soloist.

“When I came back I began to get offers. I played with the New York Philharmonic at Lewisohn Stadium, and then Grant Park in Chicago. But it takes a lot to become a violin soloist, someone like Isaac Stern. You’ve really got to want it, and love it. I loved music, and I loved to play the violin, but I wasn’t mad about the traveling, the touring, and all that.”

Stuart decided not to pursue a career as a soloist. Instead, he took a position at Oberlin College, a step up from the University of Iowa. The Canins soon had their second son. By 1966, Stuart was getting restless; he wanted to get back to playing. Offered the concertmaster position in the Chamber Symphony of Philadelphia, he took a short leave from Oberlin to test the waters. Very quickly, he decided he liked playing too much, and was not going back, no matter what happened.

Jack Benny inspects Stuart’s violin on the Jack Benny Show, 1966.

From left: Jack Benny, Stuart Canin, Paul Olefsky, & Ralph Hersh.

CALIFORNIA

Agnes Albert, one of the grand ladies of San Francisco, and an ardent supporter of the San Francisco Symphony throughout her lifetime, had a son-in-law who was a cellist on tour with his quartet. One night, after seeing a performance by the Chamber Symphony of Philadelphia, he phoned Agnes and told her, “You have to hear this man play.” Mrs. Albert got word to Seiji Ozawa, the vibrant new conductor for the SF Symphony, who arranged an audition. “I flew out to San Francisco, kind of secretly,” recalls Stuart. “I met Ozawa in a hotel, played for him—and he said, ‘Okay, you’re the guy.’”

The Canins moved to San Francisco in 1970, bought a house, and raised their two sons. Stuart played with the SF Symphony for ten years. Highlights of this period include several world tours to Europe, Russia, and Japan. “Ozawa believed in my playing, so he gave me a chance to play concertos. I played in Vienna and Berlin—big stuff!”

Stuart with composer Zoltan Kodaly.

By 1980, the Canin’s two boys were both in medical school, and Stuart needed to make more money to pay for it all. Many of his New York musician friends, who had moved to Hollywood, encouraged him to come down to work in the studios. The Canins sold their house in San Francisco and settled in Westwood. Stuart began working immediately, and after a couple of years became a sought after concertmaster.

As concertmaster, Stuart was responsible for putting together the string section. “The contractor would call me and ask for my preference in terms of who I wanted in the section. That’s the way it works.” Stuart’s reputation with the SF Symphony made him popular with the top film composers. Over the next 16 years, he played on 650 titles, including Forrest Gump, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Die Hard I & II, and Indiana Jones. His jazz and pop credits include a violin solo for the jazz group, The Yellow Jackets, and Paula Abdul’s 1991 pop hit, Rush, Rush.

Stuart, Mistislov Rostropovich, Seiji Ozawa.

Stuart enjoyed the musical challenges of recording work, as well as the paycheck. “This is music that you play once, and then never see again, unlike a Beethoven symphony, which you’ll see periodically. It freed up the imagination because you have to find out what the screen is showing at that moment, and what you should do in terms of music that will enhance what is on the screen. Being in the position of concertmaster, if you have a solo, you have to do it pretty well because you can’t keep doing it over and over again for the recording. And then they would always ask me to come into the booth and listen to the playback to see what I could hear. They always expected that. It was an interesting life.”

By the late 1980s, Stuart was ready to branch out from film and studio work. “Your imagination can roam a little bit with film music, but after awhile—it’s not Beethoven, it’s not Brahms—it’s these guys. But I never had a moment’s doubt that I was interested in it.” Stuart became concertmaster for the Glendale Symphony, and the concertmaster/contractor for the Los Angeles Master Chorale. In the early 90s, when San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum acquired Jascha Heifetz’s world famous Guarnerius del Gesu violin, “The David”, Stuart was asked to play a concert on the instrument. His brother, Martin, came from New York to accompany him on piano.

Stuart, Virginia, Aram, and Ethan, in 1987.

In 1992, Stuart was a founding member of the New Century Chamber Orchestra. Because of his reputation from his days in the SF Symphony, it was thought he could attract a group that might succeed. The concept of a string orchestra with no conductor appealed to Stuart. “It put the pressure on us to perform.” The NCCO began to give concerts, and for the next four years, Stuart commuted back and forth from LA to the Bay Area.

During this time, Stuart had a violin and speaking part in the Robert Altman movie, Shortcuts. “It was based around a string quintet called the Trout Quintet, after the famous piece by Schubert. You see us playing on screen, and then we have a little conversation. On the internet, they list the actors and actresses in it, and right down there it says, ‘Stuart Canin plays himself.’”

Stuart continued to work in LA, but juggling his recording and NCCO schedule became too much. In 1996, he played his last session, a score by John Williams. “We decided to move back to San Francisco. My wife always wanted to move back. For the next few years, Stuart describes himself as semi-retired.

In 2000, when the Los Angeles Opera appointed Kent Nagano as conductor, he asked Stuart to be the new concertmaster. Stuart was excited by the challenge, and in 2001, the Canins rented a condo directly across from the concert hall, thinking they would be in LA for a year. Instead, they stayed for nine. “I loved it! Working with Placido Domingo and Kent Nagano—that was very nice for a professional musician.” Kent Nagano stayed until 2005. His replacement, James Conlin, asked Stuart to continue. When Stuart left the Los Angeles Opera in 2010, Conlin and Domingo announced that, in perpetuity, his chair would be called the Stuart Canin Concertmaster Chair.

Placido Domingo and Stuart.

Eventually, at the tender age of 84, after finishing 3 Wagner Ring Cycles, Stuart thought he might like to slow down.

“I said to myself, ‘You’ve been here 9 years. Even though you don’t like to think about it, you have fewer days left’.” Stuart retired from the opera, and the Canins returned to San Francisco. They soon realized they should be in Berkeley so they could be closer to their son, Aram (now a doctor), and their grandchildren. “As you get older you want to be near your family. He has a nice house a couple blocks away.” Stuart’s son Ethan, after graduating from medical school and becoming a physician, changed professions and became a successful author. He currently teaches, coincidentally, at the University of Iowa.

Stuart’s advice for young musicians? “Practice, and above all, you’ve got to love it. You have to really want to do it. This is not a half-way situation. You’ve got to love what you’re doing. Music is a great profession, but you’ve got to have something to offer. That’s what I would say, in terms of your ability. That would be it.”

On December 1st, 2012, Stuart will be playing the Brahm’s Concerto with the

Livermore Symphony.