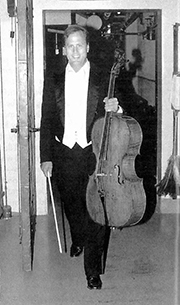

David Kadarauch, Principal Cello, “It’s Always Very Exciting.”

by Alex Walsh

“I love Wagner, so any Wagner opera is very memorable. I remember St Francis of Asissi by Messiaen, which is a great 20th century opera. We did that about 12 years ago. But basically I like them all. It’s always very exciting; opera is exciting.”

“There is a bit of a union background in my family. My grandparents were immigrants from Europe in the bad old days when there were no unions. My grandmother joined the textile workers union at the beginning of the 20th century. She went up against JP Stevens, a big textile company that didn’t want to unionize. That was the mother of all union struggles, it was horrible. Her sister, my great aunt, helped organize the Clairemont Hotel back in the 30s.”

David’s parents were not in a union. His father played in the army band during WWII, and eventually ran an animal feed and beer distributorship. “Coming from Freeport, Illinois, there was a big market for animal feed. The beer was separate because they happened to get the license to distribute Pabst beer.” His mother, a pianist with a degree from Eastman, was a housewife. The family’s musical talent was passed on to David’s children. His daughter, Katie, is a violist with the San Francisco Symphony, and his son, Alex, is a choral director. David’s wife, Anne, is a retired violin teacher.

“When I was a boy I was given the cello because my family needed a cello to round out our ensemble. My father played violin and trombone, my mother played piano, and my older brother played violin. I didn’t object but I didn’t like it. I would rather have been outside.” When he was 13, his parents said they would pay for cello lessons if he promised to practice. They found a teacher in a town 30 miles away, and took him once a week.

Music always came easily to David. In high school he entertained the idea of being a school teacher, but when he auditioned for the Curtis Institute of Music and got a full scholarship, he decided he would be a musician. He spent four years in Philadelphia, learning his instrument and playing his first operas with the Philadelphia Lyric Opera Orchestra, a small company with a pick-up orchestra. He also played local clubs and theaters for various acts when they needed strings.

In 1970, David was given a Fulbright Scholarship to study in Vienna, which was a culture shock. “I had studied German, but on the first day I didn’t understand anything anyone was saying, not one word. So that took a little getting used to.”

In Vienna, David went to an opera or concert almost every night. During the day he took classes and had plenty of time to focus on his instrument. “That’s when I really raised myself to a professional level. I learned to play the instrument very well, technically, at Curtis. But it was helpful for me to go to Vienna to try to absorb the music and flavor of the city where so much of the classical repertoire was created. I had a lot of time to think about what I was doing, an important stage in a musician’s development that should not be by-passed.”

After Vienna, David spent a year freelancing in Philadelphia while he took auditions. “San Francisco was the first audition I took, and I was lucky enough to get it. There were seventeen people that auditioned for that position. The days of hopping a jet and flying around and taking auditions were just beginning. Today when they hold an audition there might be 100 or more applicants, even a couple hundred for certain instruments. So it’s much more difficult.”

David joined the San Francisco Symphony as a section cellist. Seiji Ozawa was the conductor. “It was very exciting to step right into that job. Ozawa was a huge talent.” In the off season, David played the SF Symphony’s Music in the Schools program. “In those days, many players played in the Symphony and the Opera, and those players who didn’t play with the Opera were offered concerts in the schools. So I did that for a couple of years until I got into the Opera in 1974.”

After Davies Hall was built in 1980, the musicians had to make a choice to go fulltime with either the Symphony or the Opera. David served on the negotiating committee when the Opera and Symphony split. They succeeded in expanding the Opera contract and creating a full time living wage for the musicians. “It was a good experience, but my strength is in music and not negotiating, so I haven’t pursued it since.”

“I chose the Opera and never looked back. I wanted to be a principal player. It’s an exciting job for a principal cellist because there are a lot of cello solos in the opera repertoire. I’ve enjoyed playing them.The director at that time, Kurt Herbert Adler, made it clear that he wanted me in the Opera, so that was very flattering.”

“It’s trickier playing opera. You have to keep your wits about you because anything can happen at any time. If the singer goes astray and the conductor has to adjust–it’s a little bit different than playing the symphonic repertoire. In some ways more difficult, different anyway.”

David began playing in the SF Ballet as principal cellist in 1982, and recently retired when he turned 65.

“I was able to start collecting from our wonderful AFM union pension. If you’re 65, they allow you to take your pension even if you’re still working, which is a very good deal. A lot of pension funds don’t let you do that.” He lives in Mendocino now with his wife Anne and keeps a small apartment in the East Bay during the opera season.

His Opera and Ballet schedule did not conflict because they both use the War Memorial Opera House. “The opera season used to go into the fall, then the winter ballet season would start right up. We’d do Nutcrackers and the ballet season until May, take a short break, and then the summer opera season would start up. So it was and still is possible to do both.”

Like many musicians, David took full advantage of the recording work available during the 70s and 80s. In the 70s he played on many commercials, including a Marlboro commercial that gave him years of residuals. In the 80s he played on the first session at Skywalker Sound. His movie credits include Soap Dish, Mars Attacks, and Once Upon A Time In Mexico. Over the years he has also played on the occasional video game soundtrack. Though he was glad for the work, he says he wouldn’t want to do it full time and was never tempted to move to Los Angeles.

Throughout his career he also played many chamber music concerts, and taught privately. “I’ve had to cut back as I get older. I don’t have the stamina that I used to. I used to play a three hour opera rehearsal in the morning, then do a three hour chamber rehearsal, then go back to the opera house and play a three hour opera at night. I just can’t do that anymore.”

At 67, David says he’s taking it year by year as his health and playing hold up. “If either one of those starts to go then there’s no reason to continue. I’ve signed up for next year to keep playing in the Opera, but if by December my playing has suddenly deteriorated, then I’ll retire.”

For younger players, David’s advice is to make sure they really want to do this because it is much harder than it was 40 or 50 years ago. “There’s more competition. You have to be patient until you get a job. It can be heart breaking until you do. 50 years ago, there were more jobs. There was a thriving freelance scene when I first got here. You were able to make it by putting the pieces of the puzzle together. What you’re left with are the few big jobs, which pay well, but they’re very hard to get into. And now, there seems to be an epidemic of non-hiring; orchestras hold auditions and then end up not picking anyone. They’re getting very picky. That didn’t happen so much when I was young. They always seemed to hire someone. People were getting jobs. So it was a little easier back then.”

“I’m grateful to the union for standing up for musicians’ rights, trying to get good contracts, and making it possible for musicians to earn a living. “I know it was a struggle back in the 50s and 60s, and even earlier. That was before my time. We are now reaping the benefits of that struggle, so I am grateful for that, and always will be.”

Katie Kadarauch: “I Love Knowing He’s There, It’s Fun.”

Katie Kadarauch is a violist in the SF Symphony. She studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music, the New England Conservatory of Music, and the Colburn School in Los Angeles. During this time she travelled the world playing concerts with her string trio, Janaki. She auditioned for the SF Symphony when she was 27, and now holds the 3rd chair Assistant Principal position.

Katie Kadarauch is a violist in the SF Symphony. She studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music, the New England Conservatory of Music, and the Colburn School in Los Angeles. During this time she travelled the world playing concerts with her string trio, Janaki. She auditioned for the SF Symphony when she was 27, and now holds the 3rd chair Assistant Principal position.

What was it like growing up in a household with professional musicians?

It was fun. It was normal, because that’s all I knew. I learned a lot about classical music from a very early age. I knew a lot about certain pieces because I would see my mom teaching and my dad practicing. They had music on all the time, or at least in the car. It’s all I wanted to listen to until I was 14. At the very end of junior high I started listening to pop music.

When did you start playing?

I started on the piano when I was 5. My mom taught violin so I gravitated towards that, and the cello. I played in the Oakland Youth Orchestra on cello and went on tour with them. When I got to high school, my mom handed me a viola and said, “Try this!” And I was like, “No!” She literally made me play some chamber music, she didn’t make me, but, I did, and I loved it. Viola just clicked and I took off with it. I played viola in the SF Youth Orchestra for 4 years as Principal Violist.

What’s it like being the daughter of a famous celebrity?

It always made me so proud. I always thought he was so famous when I was younger because people would say to me, “Oh, you’re David Kadarauch’s daughter.” He wasn’t famous, but he was well known and respected here. It was fun. I looked up to him. He has a great work ethic; just naturally. He never missed any shows.

Did he give you any pointers or advice? Did you have any musician to musician talks?

He used to teach me the cello for a year or two. Not as much as you’d think, though. My parents were the opposite of the helicopter musician parents. If anything, they recognized and were supportive and happy for me, but they just wanted to let me find it myself. They didn’t need to live vicariously through me.

He’s a great role model. He has a very intelligent way about him. I think he’s done that organization very proud, both the Ballet and Opera. I think they love him. He’s certainly played a huge part in making everything accessible to me. If I liked a piece I heard on the radio, when I was eight, he’d buy it for me. He was very supportive without being pushy. In seven years at the Symphony I’ve run into him maybe 4 or 5 times on the street. Isn’t that funny? Throughout my career I have called him up and asked him what he would do, because it’s an emotional business. Last month we had coffee. I love knowing he’s there. It’s fun.