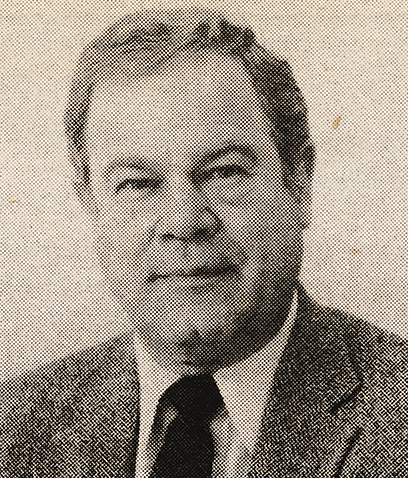

Jerry Spain was born in Omaha, Nebraska, the son of Arthur & Victoria Spain. He served honorably in the United States Army and saw combat in both World War II and the Korean conflict.

Jerry Spain was born in Omaha, Nebraska, the son of Arthur & Victoria Spain. He served honorably in the United States Army and saw combat in both World War II and the Korean conflict.

A life-long musician, Jerry started out as a Big Band player, playing the string bass. He moved to San Francisco in 1954 and worked as a musician. It was at this time that he joined the American Federation of Musicians, Local 6. He played countless shows at the Curran Theatre & with the San Francisco Symphony. From 1966 to 1984, Jerry held key roles within Local 6, rising from board member, VP & lastly to President in 1972. Jerry’s many contributions made a lasting impact on the San Francisco Symphony and the San Francisco Arts community.

Mr. Spain left the AFM in 1984 and joined the SF City Attorney’s office as a Deputy City Attorney, where he represented the City’s interests honorably and well until he announced his retirement in 1992. Shortly before he left the office, he was honored by the City with a day dedicated in his honor of his service to the City and the Arts.

Always an innovator & adventurer, Jerry had many passions outside of music & law, including several successful ventures in real estate, & a passion for private aviation. Upon retirement, Jerry moved to Kona, HI with his wife, Dottie Spain. They traveled the world together, indulging in the culture & food of numerous continents and countries.

Donations in honor of Jerry may be made to the San Francisco Humane Society. Please email jerryspainmemorial@gmail.com to share in any memories you may have of Jerry.

*Published in the San Francisco Chronicle on Dec. 7, 2018

Local 6 President from 1972-1984, Jerry Spain presided over a major transition mandated by the AFM which affected the way the local did business. Longstanding verbal agreements between the union and its many employers were breaking down as changes in labor law started to take effect. Many of the rules and regulations regarding musicians pay and working conditions had been established during the Big Band era of the 1930s and 40s when the Musicians Union was the only game in town. If an employer did something wrong, the union had sufficient authority to keep employers in line. By the time Jerry Spain took office the AFM had mandated that local unions pursue collective bargaining agreements with employers, large and small, a new tactic that required keen negotiating skills and an understanding of labor law. Having put himself through law school, Jerry Spain was uniquely qualified to bridge the

old-school approach with the new era of the CBA.

As the old verbal agreements with restaurants, hotels, and clubs in the Bay Area disintegrated, the classical world was waking up to the idea that CBAs worked well for musicians, and Jerry was right there helping them negotiate their first CBAs. He also pushed the Local to embrace women in leadership roles and encouraged Diana Dorman, Carole Klein and Melinda Wagner to run for the Board of Directors.

Melinda Wagner

Jerry was a doer. He was an extremely bright guy. He went to law school at night and became a lawyer. We were ahead of others in the field because not every local had a lawyer as an officer. The main thing he did was promote the development of CBAs with all of our employers. He was aggressive in seeking those and negotiating them. He tried to get the business agents to have skill in that area, but it was very hard. He changed the look of our Board of Directors by being proactive about getting women to run.

Diana Dorman

He was the only one trying to get women to be on committees and get involved.

When I first joined Berkeley Symphony there was no contract. You were always finding out that somebody next to you was getting paid differently. You would think you had a job, but then the contractor would not call you for something and she would say, “I called so and so because I owed them a favor.” So, I went to Jerry and said we need a contract over there. He called them up and he did it. He was out and about with every little group.

One time I contracted a ballet thing in Oakland and I used some Berkeley people and some Oakland people and I didn’t get a check. I had negotiated with a woman, so I assumed she would be trustworthy. I went to Jerry, and even though I always used a contract, he said, “Let this be a lesson–you can’t always trust somebody because they’re a woman and you’re a woman, you can’t trust anybody, really.” I took that to heart. He went after her and we got paid. He was just a great resource and he was always there. I have a great amount of respect for him. He was very funny.

Wendell Rider

Jerry Spain was the face of Local 6 and the face of all serious music making in the Bay Area. He was an incredible person and known to be tough as nails. No one stood up for the union more than him. That’s why he never had to campaign for office. He took Local 6 from okay to top of the line. In 1970, when we were negotiating the Oakland Symphony contract, he taught us how to organize, how to strike, how to do a picket line, and how not to create more problems. He was a man of action.

Bob Hubbard

Jerry encouraged us to start the Midsummer Mozart Festival. He was a no-nonsense business man, one of the good guys. He was happy to see something happening and tried to help us anyway he could.

Stuart Gronningen

I was present at orchestra meetings with Jerry over contract negotiations and strike votes. He certainly was a straight shooter, realistic about the pros and cons of strikes, and a good negotiator with management. And he almost always carried a lit cigar.

Gretchen Elliott

He changed the representation of the union. He wanted women on the Board. He was an inveterate cigar smoker. Maria Kozak told me he ran a tight ship. They had a lot of employees in those days because there were no computers. You had to have a neat desk apparently, because he would just go and knock everything off someone’s desk and tell them to clean it up. I couldn’t have worked for him!

Errol Kuhn

Jerry Spain came to speak to the Oakland Symphony in 1970 when we were having negotiations. We’re all on stage and Jerry was pacing back and forth, smoking a cigar. He was an old-fashioned union organizer, a classic figure almost as if he was from the 1930s–tough and verbal and call them like you see ‘em. He said, “You know and I know that the Board would like you to play for free. And you know and I know that that’s not going to happen.” He told us what one board member said: “Why respect musicians? With all their education they could be doctors or surgeons. It’s hard to deal with them because they don’t live in reality.” Jerry’s attitude was: We’re going to fight them. He convinced management that it was their civic duty to support us. The end result was we got a contract.