@2006 John Swanda

Swanda & Schindler Photography

109 Geary St. 3rd floor

San Francisco CA 94108

swandaschindler.com

john@swandaschindler.com

Glenn Fischthal, Trumpet: The Right Man For The Job

by Beth Zare and Alex Walsh

Glenn Fischthal is the former principal trumpet of the San Francisco Symphony (SFS). Prior to his time in San Francisco he performed with many orchestras including the Cleveland Orchestra, Kansas City Philharmonic, and the Israel Philharmonic. He recently sat down with our Secretary-Treasurer, Beth Zare, for a conversation.

Beth: I know you were principal trumpet for many years in the Symphony but what made you choose San Francisco?

Glenn: I played principal for 24 years and then 8 as the Associate. Years ago Peter Pastreich, the [SFS] Executive Director, had his secretary call to ask me to audition for Edo de Waart. He’d heard about my performances in Europe with the Israel Philharmonic. I had just come back to the States from Israel to play with the San Diego Symphony. I was happy as punch in San Diego; the orchestra was good and the schedule was easy; sometimes we only had 3 concerts a week. It was like summer camp compared to the Israel Philharmonic. I was loving it because all my college buddies played in San Diego but San Francisco paid 3 times as much so I only got to play in San Diego for one short year.

Beth: What was it like playing in the Israel Philharmonic?

Glenn: It was amazing because they would bring in the top European conductors every two weeks. We did six concerts a week. The only time off we had was Friday night because of the Shabbat. Even then, we would rehearse Friday morning and then have a concert Saturday night, so it wasn’t even a full day off. When Zubin Mehta was in town we were recording or getting ready for tours. That experience of performing and traveling, and working with all the great guest conductors–Leonard Bernstein, Carlo Maria Giulini, Daniel Barenboim–gave me the confidence that I could play principal in America.

Beth: So you weren’t always a principal player?

Glenn: San Antonio Symphony was my first gig and I was 2nd / Utility. After the first season, I didn’t want to go back to Texas for another year so I ended up playing with a big band in Toronto. On the gig I met this bass trombonist who was dating the prima ballerina for the National Ballet of Canada. He said I sounded great and the Ballet was going on the road and was looking for trumpets. I played some excerpts from memory for the music director, and they again gave me a 2nd trumpet position. I was delighted to take the gig. It was all Tchaikovsky. We did over 100 performances each of Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, and two weeks of Nutcracker.

The good news was Rudolph Nureyev was the guest artist. He was still dancing in the 1970s. I was not familiar with the ballet repertoire at all. I played there for a couple years and then thought, ‘I can do better than this.’ I heard about a vacancy with the Hong Kong Philharmonic and while the Ballet was touring New York I played for Dr. Zipper, who was their American agent. I went over to the Mayflower Hotel played some excerpts in his room, and was awarded a contract for 2nd trumpet.

“It was 1980. Here I am, new job, new city, brand new Symphony Hall. I had been looking for a better symphony and I found it.”

Glenn with Jeff Biancalana in Davies Symphony Hall

Beth: So you went from playing in Canada to China. That seems like a pretty big change.

Glenn: When I was 17 my dad, who was a professor of biology at Binghamton University in upstate New York, got a Fulbright Scholarship to teach in West Africa. I graduated early so I could go with the whole family to Ghana. Living abroad for a year probably made it seem less strange to travel to far off places, and you have to go where the opportunities are.

Beth: Did you have fun playing in Hong Kong?

Glenn: Actually, it was a terrible experience. The orchestra was pretty bad and the conductor was a tyrant. What I didn’t know when I took the job was that this was their first professional season. Also, the guy they hired to play principal trumpet had very little orchestral training, so I ended up sitting principal under a 2nd trumpet contract. I just took the available salary and never renegotiated. Although I did get to perform the Haydn Trumpet Concerto, I couldn’t take it anymore. After playing for 6 months I had to get out of there.

Beth: Did you go straight to Israel from there?

Glenn: No, I flew back to the States and won an audition for 2nd / Utility in Kansas City. I stayed there for two years. My teacher Tom Stevens recommended I audition for the Israel Philharmonic. Zubin Mehta was the conductor of both the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Israel Philharmonic and they had a vacancy in Tel Aviv. I played for Zubin at the LA Civic Center. This time there were only two candidates and I was offered the job for principal. Zubin was taking a chance on me because I was a 2nd in Kansas City, not a principal player. I accepted the job and played in Israel for 3 years.

Beth: What was the best thing about playing with Zubin Meta?

Glenn: Zubin liked to play pranks. He was one of the few conductors that enjoyed playing pranks. One of the pranks he played was on Isaac Stern. He was performing the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto with us. At intermission I hear on the PA, “Glenn Fischthal to the Maestro’s room.” Usually that means I messed up. I’m thinking, ‘Oh God, what did I do?’ When I knocked on the door Zubin said, “Oh Glenn, I want to play a joke on Isaac Stern and I need your help.” Much relieved I said, ‘Great! What do I do?’ He said, “You know the bassoon solo in the third movement? I want you to play it instead of the bassoon.” So, the next night we are playing the concerto and Zubin starts to smirk about 5 minutes before we even get there because he knows what’s coming up and he can’t contain himself. We get to the spot and I play it instead of the bassoon. Issac Stern responds by turning around and glaring at me. Zubin’s on his podium laughing.

Beth: Did you ever prank Zubin?

Glenn: I did. One night when we were playing the Beethoven Leonore Overture, which has an offstage trumpet solo. Usually conductors don’t bring out the trumpeter for a bow because the solo happens midway through the piece. This time he summons for me and I’m standing backstage with another American percussionist who looks sort of like me. I thrust my trumpet into his hands and say, ‘Ken, go take the bow.’ He walks out and Zubin looks over and his eyes light up.

Beth: Do you think trumpet players are natural born pranksters?

Glenn: I know we were seen as trouble makers in San Francisco. We were yacking all the time and the horns and woodwinds would always turn around and tell us to shut up. Chris Bogios and I were always talking. I was pretty loose on the stand. That came from my days in Israel. Because we had so many services, the Israel Philharmonic rehearsals were kind of like adult day care. We fooled around a lot, and I brought that with me to SF. One of our personnel managers did not appreciate it at all. I used to get letters all the time about my lack of discipline.

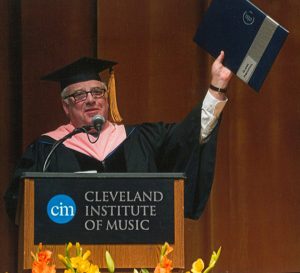

Glenn arriving at the Cleveland Institute of Music. “I am grateful to my parents for being so supportive. They always sent me to summer camps, like Aspen, Meadow Brook Music Festival and Music Academy of the West because they didn’t want me bagging groceries.”

Beth: But succeeding at music takes some sort of discipline. Was that instilled from an early age?

Glenn: My mother had a music degree from the University of Michigan but she didn’t force me to play. I actually started on cornet which isn’t really done anymore. My parents were very supportive but they said, “If you are serious about playing an instrument, you need to take private lessons, and you’ve got to practice.” They found me a teacher who came to our house. I played cornet all through high school. My mother asked me, “When you finish high school, what do you think you’d like to do?” I said, ‘I enjoy playing the cornet, it’s inspiring when people come up and tell me they enjoy my playing.’ She asked, “Why don’t you apply to some conservatories?”

Beth: Where did you end up going to school?

Glenn: Remember I started at the University of Ghana. They didn’t have a cornet instructor so I studied with a Hungarian clarinetist who spoke no English. In the one year I was there I got to perform on local television with a couple of different groups. It got me into performing. I had been waiting and waiting to hear from one of the conservatories to accept me. Finally, Bernie Adelstein, the Principal Trumpet for the Cleveland Orchestra, heard my tape and I was accepted into the Cleveland Institute of Music. I was very naïve. I thought I could just major in cornet. They wrote back and said I would have to switch to trumpet because they didn’t have cornet majors.

Beth: You mean you got into music school and you had never played a trumpet?

Glenn: My parents bought me a trumpet that had a light weight bell because we didn’t know any better. The university had a 500 seat auditorium and it sounded glorious when I played mezzo forte, so I got away with it. It took a couple years for my teacher to get me to move enough air through the horn. He just kept yelling at me, “Blow! Blow!” My approach had always been like that of a cornetist–easy air, sweet tone. I couldn’t quite get what it took to be an orchestral player which requires a lot of volume and air.

Beth: What did you do after school?

Glenn: James Levine was our university orchestra conductor because he was George Szell’s assistant across the street at the Cleveland Orchestra. In 1970, just a week before my graduation, Levine asked me to sub on a piece he was conducting for Cleveland. The orchestra was scheduled to depart on tour shortly after that. Because I had just subbed, I was fortunate enough to get hired as a sub on the tour, as well.Here I am, right out of school, and I’m on the road with the Cleveland Orchestra. I was so thrilled. I thought ‘Wow, listen to this orchestra, they’re incredible!’ Sometimes I would miss entrances because I was so excited. The tour lasted 3 weeks. We went to Seattle, Japan, Korea, and Anchorage on the way back. Those were the last concerts that George Szell conducted because he died right after we got back to the States. Pretty amazing that I got to participate in them.

Receiving a Distinguished Alumni Award

Beth: What brought you to CA?

Glenn: When we got back from tour I didn’t have a job. Walt Disney was just opening the new Cal Arts campus in California. My teacher arranged for me to get a full scholarship because they needed students for the music school. I went to Cal Arts as a masters candidate. At that time, the LA Brass Quintet was in residence there and that is when I started studying with Tom Stevens.

One summer at the Music Academy of the West, we did an all Stravinsky program and the word got out that I was available. The San Antonio Symphony was looking for a trumpeter at that time so they sent their assistant concertmaster and principal trumpeter to come hear the Stravinsky concert. The next morning I was going to audition for them in my apartment. We’d had an all-night party and there were people sleeping in the living room. I got up and had to nudge them and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got some people coming over for this audition. Go to the back bedroom if you want to keep sleeping.’ I lived right on the beach. When the guys from San Antonio got there I opened the big bay windows and played some excerpts overlooking the Pacific Ocean. They had a contract in their pocket ready to go. That was the start of my professional career.

Beth: I know things are different now but do you have any advice for people taking auditions today?

Glenn: Times have changed. They don’t have invitations or single auditions anymore. It’s a cattle call. There’s just so many qualified players, so many kids coming out of school that are well trained and looking for work. It is very, very difficult but if you persevere you can get better at taking auditions.

You can’t just sit at home and practice the repertoire. You could probably sound great at home in your room. You’ve got to figure out how to manage yourself and your nerves at auditions. You need to know what to eat to fuel yourself. I remember one audition I forgot to eat and I got a little shaky towards the end. You learn all these things, including what repertoire you have problems with, where your weaknesses are by doing it. To produce an audition that the committee is going to be impressed with you just need to be confident that you’re the man or woman for the job.

“In this business you can’t really pick and choose. You have to go to where the opportunities are.”

The San Francisco Symphony Trumpet Section in 2004. From left: Laurie McGaw, Don Reinberg, Chris Bogios, Glenn Fischthal.

“The principal brass contributed to the San Francisco Symphony sound concept. Dave (Krehbiel), Mark (Lawrence) and myself were the leading brass players at the time. We had a unified sound and a lyrical approach yet it was strong. We got a lot of recognition with our earlier recordings like the Mathis Der Maler and people started listening to our brass sound on the West Coast. That became defined as its own sound, it wasn’t Chicago, it wasn’t LA, it was its own thing.”

Beth: Has anything unexpected ever happened to you during a concert?

Glenn: I was on tour once with the Israel Philharmonic at the Lucerne Festival and we started with the Forza del Destino Overture which has these big E-major brass chords at the beginning. My second slide was loose and as soon as I start to blow it pops out of my horn and goes flying across the stage and bounces around. Zubin, who conducted those chords with his eyes closed heard the dropped note and opens his eyes to see what looks like a mouse running around. It was my slide. The good news was that during intermission I was able to lock down that second slide to make sure it wouldn’t pop out on the solo opening of the Mahler 5. In a way, I was lucky it came out on the overture.

Funny thing is it was Bob Ward [principal horn in SFS] who taught me how to fix a loose slide. He said, “You know how to keep a slide in, don’t you?” ‘How?’ I asked. “A hair.” I said, ‘Really, a hair?’ So I took the slide out, put the hair on it and pushed it in. Sure enough, it locked right in there. Who knew? Bob Ward — the hair remedy.

Beth: Do you still play?

Glenn: A little bit. I’ve been asked to play assistant principal next month for the San Diego Symphony. Adam Luftman, the principal in the SF Opera calls me to play some backstage stuff. Last season I did Aida for 11 performances. When I left the SF Symphony I was looking for new adventures, having mostly played symphonic music all my life. I thought here’s a chance to do operatic repertoire which I’m not that familiar with. Also, I still play with The Bay Brass.

Beth: How did you know when to retire?

Glenn: Playing principal for 24 year in SF was a lot of pressure and eventually it got to me. I wanted less of the hot seat. When the Associate Principal position opened up I thought it would be a good fit. That’s what I played the last eight years. I would usually play the first half of the program and the principal would come out and do the tour de force piece. I was much relieved. I had already done it all and so I was happy to step down to in a lesser position and still play the first parts, but not the go for it glamour parts.

I didn’t want to be one of those guys hanging on and people saying, “Is he still here?” I wanted to leave at the top of my game, make them want more. I have no regrets about leaving. I think it was the right time for me. I enjoy retirement a lot.

The Bay Brass formed in 1995. Glenn Fischthal (far left) was one of its charter members.