Frank Martin: “I feel Blessed.”

by Alex Walsh

Frank Martin is a keyboard player, arranger, composer, conductor, session musician, band leader, and teacher. His list of recording credits include Narada Michael Walden, Whitney Houston, Herbie Hancock, Al Jarreau, Regina Bell, Tevin Campbell, and Chris Isaak. He joined Local 510 in the 1970s and is now a Local 6 life member.

“I did five records with Chris Isaak. I lucked out getting in there on Wicked Game which was a mega hit. I also did live gigs with him, including MTV Unplugged. It was a fun time.”

Frank Martin, 2015

Wicked Game was released in 1989. By this time Frank was a veteran session player, a dream he had since college. “One time Chris flew me to LA to record finger percussion on my samplers. He called me up and said, ‘We want to fly you down here to do overdubs.’ I said, ‘Awesome! Some keyboards? He said, ‘No, percussion.’ I said, ‘You’re crazy–there must be a couple decent percussionists in LA.’ He said, ‘No, no, we want to work with you.’

Early Years

Frank was born in Oakland, CA in 1949. His grandmother was an opera singer. Unfortunately, her career was cut short when her parents died. She was offered a scholarship to study in Europe but declined because she had to raise her younger siblings. Frank’s other grandmother worked as a church organist for many years, and his mother performed during the war singing for the USO entertaining the troops. His father sang in a barbershop quartet before Frank was born.

One day when he was five, Frank came home to find a piano in the house. “I remember seeing this thing in the corner. I went up to it and put my hand on it and hit the low range. I went ‘Wow, this is the coolest thing ever!”

Frank started picking things out on the piano by ear and was soon taking lessons. By the time he was a teenager he was studying with Local 6 Member, Don Burke who introduced him to jazz by playing the records of Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Toots Theilemans, and Dave Brubeck. “Dave Brubeck changed my life, because he’s about rhythm.”

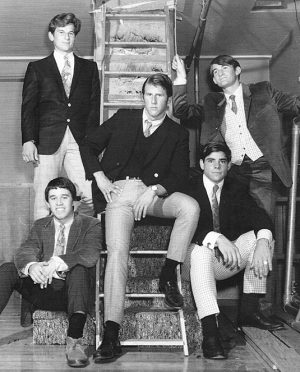

Frank attended Bishop O’Dowd High School in Oakland. In grade school he played music for fun with friends and by 11th grade was in an official band called The Trend.

The Trend, 1967. Dave Ellis (drms/bottom left) Bob Spinardi (bass/top left) Gary Fricke (gtr/center) Todd Malone (vocalist/bottom right) Frank (top right)

Frank’s father saw his passion for music and bought him a Vox Continental Organ, the kind used by Ray Manzarek from The Doors. Frank liked it but soon returned it for a Farfisa Compact Organ, used on “Wooly Bully” by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, one of the songs his band played.

The Trend played their first gig at a local event and were paid $3 each. “Paid to play? It was incredible! We thought we were hot stuff.” They played many teen dances and eventually knew over eighty songs. After high school the group dissolved and Frank formed a psychedelic rock band called Atticus. They recorded a demo with Fred Catero, the engineer for Blood Sweat & Tears, Chicago, Transit Authority, and many other bands from the 60s and 70s and beyond. “We didn’t know how lucky we were. We did three tunes with him. Who knows where that tape went?”

With the Vietnam War raging, Frank joined the National Guard in 1969 to avoid the draft. After basic training he returned to Oakland and went to school at Merritt College. He heard another member of Local 6, Art Lande, at a club in Palo Alto called In Your Ear and took lessons from him. “He taught me improv concepts and opened me up to Avant Garde playing and composing. He was into odd meters as well but in a more open sense. He was and is brilliant.”

By this time Frank’s parents were encouraging him to get a real estate license. Frank thought it was a good idea so he took business classes and then went to a private school to get his license. “I had a job waiting for me at a company but I realized I had no passion for it. Halfway through my studies a light went off and I said, ‘What the heck am I doing?’ So I decided to switch my major to music.”

1964: The Beatles at the Cow Palace

“I remember my dad had a friend at a bank who had a couple Beatle tickets. One of my sisters and I got to go. The Righteous Brothers were on the bill and three or four other acts. As soon as they said, ‘Please welcome to the stage, the Beatles!’ All you could hear was AAAHH! One loud pitch of girls going crazy. Sometime prior to the concert George Harrison mentioned the bands favorite candy was jellybeans, so everybody threw jellybeans at them while they played. It was a unique experience to hear all the screaming and watching the cops trying to keep the girls off the stage.”

Frank transferred to Hayward State where he studied Avant Garde music with pianist Julian White. “The first lesson I had he went to the chalk board and drew an eye, then an ear over here and an eyebrow over there. Then he drew another face. He said there’s no difference, you’re just juxtaposing things around. That was how he conceived music. You could turn it around, play it upside down, do all this wacky stuff. That was right up my alley.”

Frank also began jamming in the college practice rooms and was encouraged by fellow student and trumpeter Mic Gillette to try out for school big bands and small jazz ensembles. Used to being considered one of the better players, he was shocked when he was rejected. “I auditioned for a small ensemble of jazz cats and didn’t get the gig, with a little bit of an attitude from them. ‘You’re not good enough, you don’t know enough tunes,’ they said. From that moment on I started practicing and practicing and practicing, day and night. I said to myself, ‘That’s never going to happen again.’ But it was great because I realized they were right, I wasn’t ready. It’s amazing how being told no can turn your life around in a really positive way.”

Frank eventually made it into the school bands and played in many groups on and off campus. He joined Local 510 in San Leandro which kept him busy with trust fund jobs, including playing at the local prisons. A few years later, with one semester to go, Frank left school to join a progressive rock group and never came back. “I joined a band called Visions that had members of Boz Scaggs group, Malo, and Edgar Winter’s White Trash. It was a two year run. We were singing songs in 13, wacky stuff. It was a good band.”

By this time, he was playing a Fender Rhodes, a Hohner Clavinet, and an M3 Hammond Organ. He spent many hours at Don Weir’s Music City in San Francisco drooling over the latest gear and buying new synthesizers when he could afford them. Frank was able to fund his equipment purchases because his overhead was low. “My rent was $60 and PG&E was $10. I could do wedding receptions and little club dates and with the $50 I was getting here and there it was no problem making a living.”

No To Las Vegas

In 1977, Frank went to Las Vegas to sub at Caesar’s Palace and was immediately offered a job as an arranger/keyboard player. “It paid $500 a week. I hadn’t made that kind of money ever. I went home to think about it and remembered how I’d auditioned with a Top 40 band in Reno and saw all these bands at the casino playing for people who could care less. I swore I would never do that. The musicians were all making a living, and they were talented, but I saw this life where you play all these schmaltzy things, make a lot of money, and then you die. So I called the guy back and said, ‘I’m sorry but I can’t do it.’”

Frank Martin with multi keys, Narada tour, 1980

A week later he was playing with saxophonist John Handy. Frank’s friend, guitarist Steve Erquiaga, had been asked to recommend a keyboard player who could play jazz, a Minimoog synthesizer, and odd meters. “It was tailor-made for me, all the stuff I wanted to do.”At the audition, which actually turned out to be the first band rehearsal, John Handy told them they were going to LA in three weeks to make a new record and then go on tour. He didn’t have enough material so he asked the band to submit music. “I went home and wrote a bunch of songs. Two made it on the record. The album, Handy Dandy Man, didn’t do well but it was a great experience. It all came from saying no to Las Vegas.”

After the tour, Frank returned to Oakland where he recieved a message from a drummer who had just moved to the Bay Area and was looking to start a band. It turned out to be Narada Michael Walden. Frank helped Narada find local players and they soon went on tour opening for Patti Labelle and Grover Washington. The pop audiences were frequently lukewarm to Narada’s jazz fusion material, but went crazy when the band played his recent hit I Don’t Want No One Else To Dance With You. After the tour the band went into the studio to record Narada’s next album The Dance Of Life which gave them two more hits.

Narada Michael Walden Band 1979

USA Tour (Randy Jackson on bass)

“To go into the studio and make the music feel good to a click track is an art that you don’t really learn until you do it over and over and over. In the dance world it has to be on the money. I learned that craft from Narada.”

When Narada started producing artists out of the Automatt, David Rubinson’s recording studio in San Francisco, Frank became part of his production team, along with bassist Randy Jackson, and guitarist Corrado Rustici. “The Automatt was great. There was a camaraderie that happened because we all played on each other’s projects.”

“Of Course I Can Do That.”

In 1981, Narada was producing Angela Bofill, a jazz artist who was crossing over into R&B. “We did three Angela Bofill records and out of the blue she asked me, ‘Do you write for big band?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, of course I do big band writing.’ I’d never written a score in my life! So I got together with Wayne Wallace, the trombone player, and he helped me arrange four songs. Then she said, ‘I’m opening for Bill Cosby in Atlantic City and Las Vegas and I need a Musical Director/Conductor.’ Again I said, ‘Of course I can do that!’”

Pete and Sheila Band (Escovedo) at the Scarab in Berkeley, 1981. from left: Larry Schneider (sax) Pete Escovedo (perc), Joy Julkes (bass), Romi Geroso (gtr) Frank Martin (keys), Sheila Escovedo (drums), Wayne Wallace (bone)

Frank had taken a conducting class in college, and been a band leader, so he knew he could at least communicate with the musicians, but he was scared. “I remember standing behind the curtain in Atlantic City, just shaking. I said to myself, ‘Relax, breathe, and just do it.’ I walked in, introduced myself, and started with the rhythm section. I said ‘It doesn’t have to be exactly what’s on the paper, I just want it to sound and feel good.’ And they said, ‘Really? No one’s ever said that to us before.’ So I had them on my side immediately. Same with the rest of the band. It came together easily.”

After the tour, Frank was asked to put a band together for Angela in the Philippines. “We were asked to play for President Marcos at his palace on New Year’s Eve. I’ll never forget when Angela’s manager danced with Imelda (the President’s wife) and knocked her over. We all thought, ‘Oh my God, here we go! Ahh!’ We couldn’t wait to get out of there.”When they got back home Angela asked Frank to move to New York and be the Musical Director of her band. He lived in Manhattan and toured three to four days a week.

Frank returned to the Bay Area and immersed himself in the local scene. In 1985, he was hired by KPIX Channel 5 to be in the house band for a locally produced daytime talk show, People Are Talking In The Afternoon, where her co-wrote the theme song with drummer Greg Sudmeier. He also played in what came to be known as The Kanzaki Band at the Kanzaki Lounge in Japantown on Tuesday nights, a gig that lasted ten years. “The players that went through that band were unbelievable. In those days you could have a steady band. That was a great scene.”

“I was in the right place at the right time with the right gear and I happened to know about odd meters. Everything was handed to me in a cool way. I was lucky. I feel blessed.”

Back in the studio with Narada, Frank was asked to give input on Al Jarreau’s new album. “Miles Davis had just died so I suggested they do a tribute to Miles and add lyrics to it. We looked down, and there on the console was Miles Kind of Blue CD. We turned it over, saw the tune Blue and Green and said, ‘that’s it!’ I went home, did an arrangement, wrote lyrics, and recorded it overnight. When I brought it in Al said, ‘I’ve been wanting to record this forever, let’s do it!’ I gave him the lyrics and he said, ‘I’ve always tried to write lyrics to this but I’ve hit a wall, can we co-write lyrics?’ I said, ‘Can we co-write lyrics, Al Jarreau? Yes, I think we can!’ So we got together the next day and the next thing you know it’s on the album.”

Sting rehearsal for

Carnegie Hall, 2008

Frank says all of his sessions for record companies were union until they made the musicians independent contractors. “That hurt us all in a huge way. We were paid less with no pension coming in and we had nobody to represent us. The record companies were supposed to pay us within 15 days – good luck. It would take a month, two months, and even then you’d have to hassle them. It was tricky because you didn’t want to rock the boat.”

Throughout the 90s Frank worked on many union jingle sessions for producers like Ed Bogas, Chris Michie & Andy Kulberg. “They were as busy as you could ever get. We used to do a ton at Russian Hill Recording Studio and the Plant, all union stuff. It stopped because the jingle business became in-house. Guys like myself could come in and do it all. I didn’t want to start my own jingle house so I lost out on that. Other people did really well.”

Frank Martin Productions

With session work slowing down, Frank decided it was time to build his own studio so he could produce projects himself. For many years he had maintained a practice studio where he could rehearse and work out arrangement ideas, so when a space opened up in San Rafael he jumped on it. “It was an empty garage. I’ve built the studio up from scratch with help from friends over the past fourteen years. It’s been a labor of love.”

Frank Martin Group (Abe Laboriel-Alex Acuna-Marc Russo-Stef Burns), 2009

Frank says the market has changed and artists aren’t recording full albums like they used to. “Up until four years ago I was doing non-stop productions. It’s just so hard to make your money back from a CD. Now people have really small budgets so

they record one song and sell it online. I still do productions here but not nearly as much. It’s become my teaching studio and arranging oasis.”

Frank continues to do sessions with Narada Michael Walden, and play in his band. Every other year they go to New York to play with Sting at Carnegie Hall for his Rainforest Foundation. “We’ve been doing that for seventeen years now, it’s a really cool thing.”

“I’ve had a bad attitude when things are slow, but then I tell myself, ‘Go get a gig, teach, compose–then I’m back.”

Frank Martin in Japan, 2013

Giving Back

This summer, through the International Cultural Arts & Healing Sciences Institute, Frank will conduct a symphony in Kazakhstan.

“Kasakhstan is located between Afghanastan and Russia. They say it’s a safe area but we’re still going to have guards around us. They don’t speak English so we’ll have interpreters. It’s a big production. I’ll work with the orchestra for five days and then the dancers and singers will join us for three days. Then we’ll do a show. The director, vocalist Amikaeyla Gaston, arranged for us to play a jazz duet concert for the President of Kasakhstan’s birthday.”

Frank currently teaches at UC Berkeley, the California Jazz Institute, as well as summer music camps and public schools. He recently taught jazz to 5th graders in Healdsburg, an annual program called Operation Jazz Band sponsored by the Healdsburg Jazz Festival.

“I’m amazed by the enthusiasm and knowledge of these kids. The teachers give them assignments to write papers about their favorite jazz artists and they come in with all kinds of questions. We talk about the groove and all this stuff I never heard about when I was a kid. I love giving back. It’s changed my life.”

“I tell the kids that attitude is everything. As long as you’re pursuing your passion, you’re successful. It doesn’t have to be music, it can be anything. You may not get the golden egg, but you’re living a great life and making stuff along the way.”

Frank Martin in his studio with singer Tony Lindsay (Santana), 2016