JOHN MOORE: “A Versatile Bass & Tuba Professional.”

by Alex Walsh

“I’ve always said I went into this because I love music, and I love to play–I never wanted to be rich and famous. And now, after fifty seven years, I’m on plan.” — John Moore

“The music business has changed completely. I’m sorry it has, because I enjoyed a lot of things. When I was a kid, they used to tell me, ‘Well, you missed it kid. In the 30s, there were always two guys looking for you to join their band, and if you didn’t do a radio show on the way to your night job…’—Things like that. I don’t know too many wealthy musicians, but a lot of them have done just fine, having a nice life and a good family.”

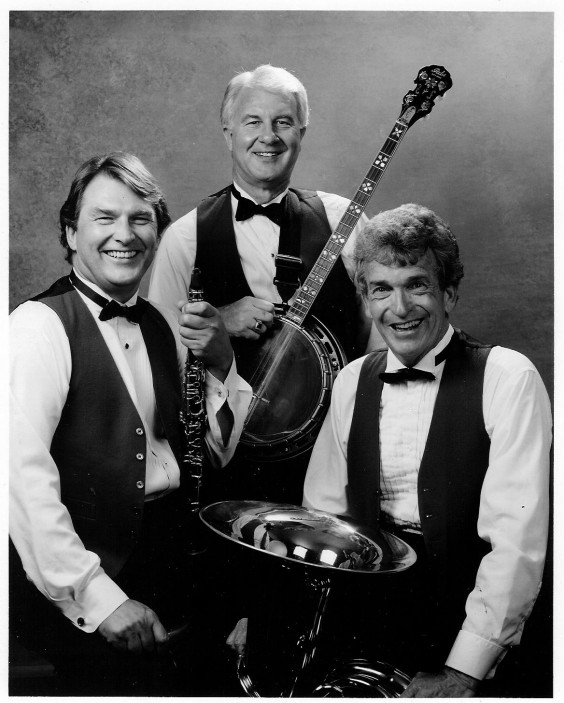

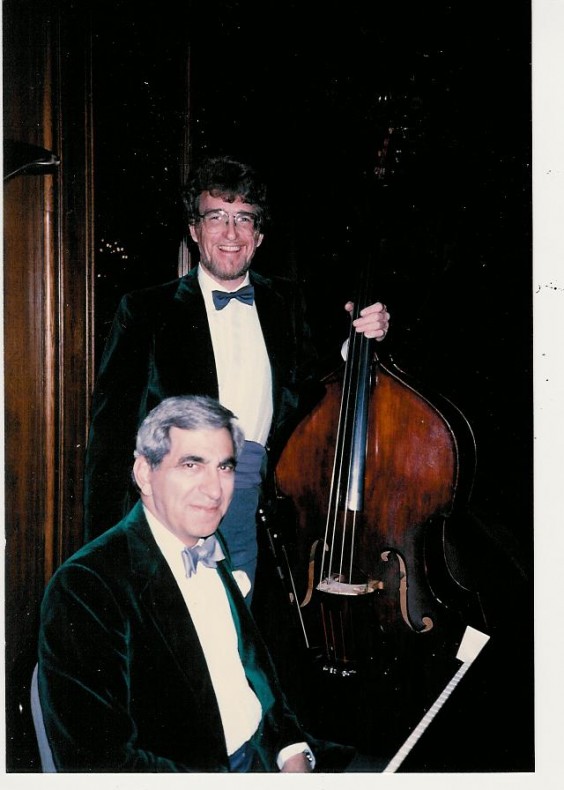

“The Fog City Trio: One of John Moore’s many groups.

From left: Dale Mills, Andy Norblin, & John Moore.

Recently retired, John joined the union when he was 16. His tuba teacher, Tony Balice, a working professional, got him work right away, working right beside him. “Ringling Brothers Circus, Pollock Brothers Circus, and we used to do the Grand National Rodeo at the Cow Palace. It was a lot of tuba playing. Circuses are real lip busters. It was fun.” John soon earned enough to buy a car.

“I played alot of gigs other than the circuses, including dances, parades and funerals in Chinatown. There used to be Trust Fund concert band jobs. We’d do a concert out by the Zoo, or Maritime Park. I eventually got into the SF Municipal Band, when George Christopher was the Mayor. They played all the city parades. If you were lucky, a second band called you for the parade. If that band was in the back of the parade, and you were in the SF Municipal Band, you could play the parade up, get a cab, and then go back and catch the second band. Play two parades in the same parade—double header. Those were big doings in those days.”

In 1959, Ralph Murray, the tuba player with the San Francisco Symphony and conductor of the Golden Gate Park Band, called John to tell him the Monterey Jazz Festival needed a tuba player, and asked if he could do it. John says he had no idea what he was getting into. “When I got there, I ended up playing with Gunther Schuller, for his Symphony for Brass and Percussion, and with John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, and JJ Johnson. That was a great experience.”

A CITY GUY

John was born in San Francisco in 1941. His mother, Frances, a graduate of Stanford and Cal, was a public school teacher in the SF Unified School system for thirty five years. John’s father, Thomas, was a roofer. During WWII, he helped build naval ships in the Bay Area. He was elected secretary-treasurer for the Roofer’s Union, Local 40, after a bus accident left him unable to do heavy work. Eventually, he served as president, and later held statewide offices for the Roofer’s Union.

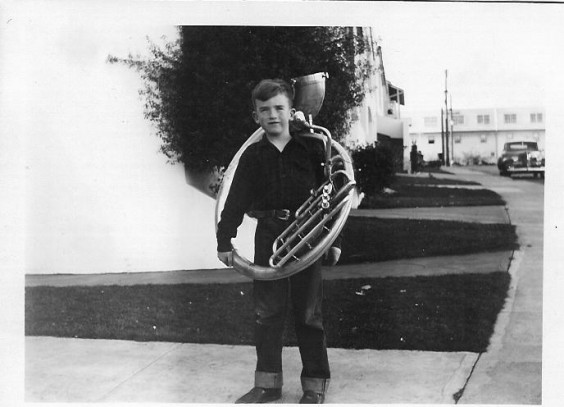

John, age ten, with his sousaphone.

A few months before he was born, John’s parents bought their house in the Glen Park neighborhood of San Francisco for $6,000. Neither of his parents were musical, but John found something in a big case in the basement, left by one of his dad’s brother’s, that intrigued him—a sousaphone. In junior high, he started on tuba, and began private lessons with Tony Balice. “My folks were very supportive. My dad used to drive me over to my lesson once a week. Dealing with a tuba when you’re a kid on the bus is never easy. And then he used to drive me down to the San Francisco Boys Club band rehearsal once a week.”

Eventually, Mr. Balice gave John his string bass, telling him he should learn that as well. “In the old days, where he came from, you had to really do both, whether you were going to play shows or dances. The tuba had a few special jobs that it did all the time, and the bass the same way. By the time I got to high school, the electric bass guitar had started being used, and I got one of those.”

John attended Balboa High School where he was a class officer and graduation speaker. Although he fully supported John’s musical activities, his father encouraged him to find a vocation. John became interested in journalism and photography for the school newspaper. “My dad always said, ‘music is a great sideline, but give yourself a vocation.’ So, I thought advertising would work.” After graduation, John went to San Jose State as a journalism and advertising major.

PIZZA AND BEER

John began college in the fall of 1959. “I made the mistake of going over to the music department and asking, ‘Hi, what’s doing?’ They said—‘You’re a tuba player?’ Of course, tuba players are kind of rare. Before I knew it, I was playing first chair in the college band, the orchestra, and everything.” Along with his advertising and journalism classes, John took classes on musicianship and arranging. He met his future wife in the music department. They got married and had a baby. John realized he needed to start working.

“I started playing at pizza parlors, where they had Dixieland bands. There was a trend of pizza parlors with music at the time. A tuba is one thing you can use in a Dixieland band. The idea was to get people singing and drinking. Beer was a dollar fifty a pitcher. And pizza was cheap and high profit.”

John started off playing a few nights a week, but he was soon playing six nights a week—sometimes more—while going to school fulltime. “I don’t know how I made it through that period. That went on for five years.”

He was a regular at Big Al’s Gas House in Palo Alto and played occasionally at other local hot spots, including the Red Garter in San Francisco. “There were lines down the street in those days. We used to play twenty minute sets. They didn’t even have pizza at the Red Garter, just beer and peanuts. People would have a few beers and sing. The band would be, maybe, three banjos, a piano, and a tuba. We wore red and white striped vests, white pants and white shirts.”

At San Jose State, in addition to music, John was active in the journalism and advertising department. He worked on The Spartan Daily, the school daily newspaper, and was the advertising manager for Lyke, the award-winning school feature magazine. “I was a busy boy,” recalls John. As an advertising major, he was required to do an internship at an agency. When he graduated, the agency hired him fulltime. About this time, the lease was up on Big Al’s Gas House. “So I went to work in advertising, with music as a sideline. Then I started playing nights and weekends, and other miscellaneous casuals, at the Red Garter and other places.”

BASEBALL

John lasted eight years in advertising. He was vice-president until 1973. “The pressure was just crazy. I had a lot of things going. The guys I worked with were very creative. One of them created the Pet Rock. The owner of the agency financed it for him.”

By the late 1960s, John was a regular in the Red Garter Band. Along with club dates, they played the 49ers games at Kezar Stadium, and then Candlestick, for four years. They were eventually hired to play for the Giants. “Up until then, Del Courtney’s fifteen-piece band played in the bleachers for the Giants games on weekends. When management wanted to try something different, they came up with the idea of having three five-piece groups. The Red Garter Band was one of them. They also had a mariachi band, and a jazz band with Dino Bennetti. We strolled in the ball park during the game, and a little bit before.”

In 1968, the A’s came to town, and John joined the Oakland A’s Swingers. “That was every home game for the longest time—aproximately fifteen years. There were, like, sixty games. Over the years it dropped down to half of that. If I had a night job or a good wedding, I could sub it out. I had a good sub.”

John also played electric bass late Sunday afternoons in Tiburon at a place called 39 Main. “That was kind of a half sing-along. Every weekend would be at least two baseball games, that job in Tiburon, and one or two night jobs on Friday and Saturday nights.” Because these jobs were covered by union contracts, they paid pension.

In 1972, the A’s made it to the World Series. The owner, Charlie Finley, brought the Oakland A’s Swingers along. “He was kind of a wild man. He took us to the playoffs in Detroit, then to Cincinnati for the World Series. He was a character. It was two weeks of flying back and forth, but it was fun. And then he took us to New York the following year. That was a really unforgettable experience.”

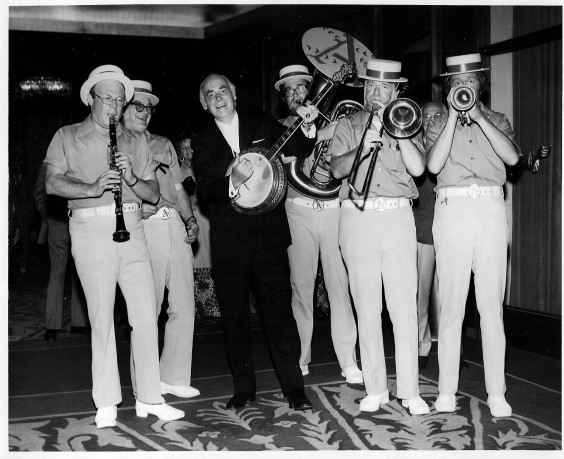

The Oakland A’s Swingers with A’s owner Charlie Finley

The Oakland A’s Swingers with A’s owner Charlie Finley

on the way to the World Series.

From left: Bill Napier, Dick Oxtot, Charlie Finley,

John Moore, Bob Mielke, Jim Goodwin.

When he left the advertising agency, John worked part time for a music contractor, Johnny Vaughn, from whom he learned how to sell jobs and be a contractor/leader. He put together a group with his wife, Eunice, so they could do weddings and Bar Mitzvahs. “She was a good singer and also played piano. I played bass and a little valve trombone, and we got a drummer. Weddings and Bar Mitzvahs were good because we made much more than sideman’s pay. I’m sure I’m starting to sound like a money hungry bastard, but by then we had two daughters, and a house, and cars to pay for.”

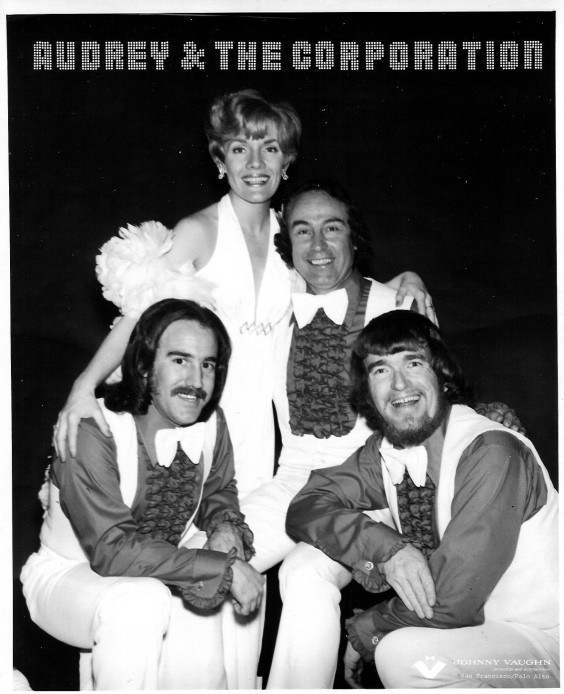

In the mid 70s, John joined up with a friend’s group, The Corporation. They added Audrey Holmes, a singer, and auditioned for the Top of the Hilton in San Francisco. They ended up doing five nights a week, Tuesday through Saturday, for five years, while Margie Baker did Sundays and Mondays. “Audrey didn’t last long. Then it was Marie & The Corporation, then Linda & The Corporation, then Carol & The Corporation.”

Audrey & The Corporation, 1975:

Dave Daly, Audrey Holmes, Walt Flory, John Moore.

John and Eunice sold their house in San Jose in the late 70s and bought a bigger house in Montara to raise their growing family. A few years later, they divorced, and John moved back to San Francisco to help his ailing mother.

HOTELS, CONVENTIONS, & CRUISES

In the 80s, John continued to work baseball games, football games, and casuals. He played nine years with Abe Battat, five nights a week, at the Compass Rose in the St. Francis Hotel, one of the last union hotel gigs in San Francisco. By this time, the hotel agreements with the union had fallen apart. More than most, as a contractor, John understood what was happening: “The hotels wouldn’t sign any more collective bargaining agreements with the union. How they got around that was that several agents became suppliers of music. When I was at the Hilton (working under a union contract), I was the leader. I used to do all the steward reports, so I knew how things went. After that job ended, another band came in, working under an agent. They were making half of what we made. The hotels and agents didn’t have to pay any federal tax, employer tax, or pension, and we became independent contractors. That one really hurt. All the non-union bands came in, and the agents didn’t want anything to do with the union. They didn’t want to hear anything about scale as long as you’d work for their money. And that was a real bad thing.”

With Abe Battat in the 1980s.

By this time, the 49ers had stopped using a big band inside the stadium at Candlestick, and John was hired for one of the strolling bands that entertained the fans in the parking lot before the games. During this period, he also played many conventions, at one point working eleven gigs in three days— “three breakfasts, three lunches, three evenings, and two cocktail hours. It was a big bankers convention, and they had stuff all over town.”

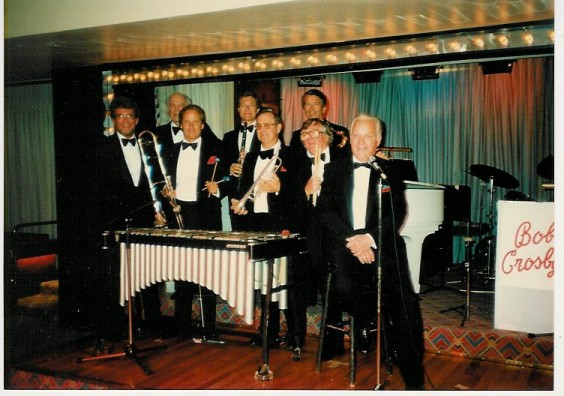

John worked a few cruise ships during the late 80s and early 90s, including a month long cruise with Bob Crosby’s Bobcats (Bing Crosby’s brother). “Most of them were Dixieland oriented cruises. You’d get very little money, but you got the cruise, and then you’d work one or two concerts a day. Some of them were a lot of fun. I went to Hawaii, Alaska, Mexico, and the Carribean.” During this time, John also played the first Sacramento Traditional Jazz Festival.

Cruisin’ with Bob Crosby’s Bobcats.

From Left: John Moore, Oscar Franson, Rex Allen, Jim Rothermel,

Tom Leps, Alex Massey, Dave Black, & Bob Crosby.

In the 90s, John started playing in the Golden Gate Rhythm Machine, a tradional jazz band, that played many jazz festivals around the counrty. He also started one night a week at the Gold Dust in San Francisco, a job that lasted seventeen years. In the recording realm, John says he’s made about fifteen recordings over the years as a sideman on various tapes, LPs, and CDs.

NAME THAT TUNE

“One thing about my career, if you want to call it that, is I’ve been very lucky to have long runs.” John played the Giants games for twenty five years, and the A’s games for twenty four. “Near the end, we didn’t even play in the stadium. They had us out in the parking lot. By then, they’d been putting in jumbotrons and big sound systems, so they didn’t need us between the innings, or anything like that.” The 49er strolling gig lasted eighteen years. To fill his calendar, he started playing Sunday brunches at country clubs and hotels.

His Tiburon job went for forty five years—“fifteen years at 39 Main, then we moved down the street to The Dock, and that totaled thirty years. When The Dock closed we went to Marin Joe’s in Corte Madera. That ended about four years ago. We played so soloists could get up and sing with us, instead of for group singing.”

“I played many different kinds of music besides jazz and standards—light classics, bluegrass, show tunes, country and western, international, brass choir, and oldies pop and rock. Lots of wonderful music.”

A Hawaiian band John put together for the San Mateo County Fair:

Jon Eriksen, vibes, Jeff Neighbor, vocals & ukulele,

John Moore, bass, Lisa Sanchez, guitar, Shota Osabe, pedal steel.

In the 2000s, John was hired to put together a band for the San Mateo County Fair. “You talk about knowing a lot of tunes—we had a five-piece Dixieland band: banjo, tuba and three horns, soprano sax, trombone, and trumpet. I challenged the boys—I used to pass it around and have them call tunes. I said, ‘let’s see how far we can get playing a different tune. Each tune is a different one, unless we get a request from the crowd. Let’s see how far we go.’ We made nine days, three hours a day, without repeating.”

For years, John volunteered on the Local 6 Casual Wage Scale Committee. He also participated in the Local 6 video project of the late 90s. He retired recently, due to health reasons, and is very thankful for the AFM pension. “Just the pension alone is worth every penny and every effort I’ve done in the union. I was very fortunate to be able to make a decent living and keep busy—and get my dear children through school. They have families now, and I have grandkids, and everybody’s happy.”