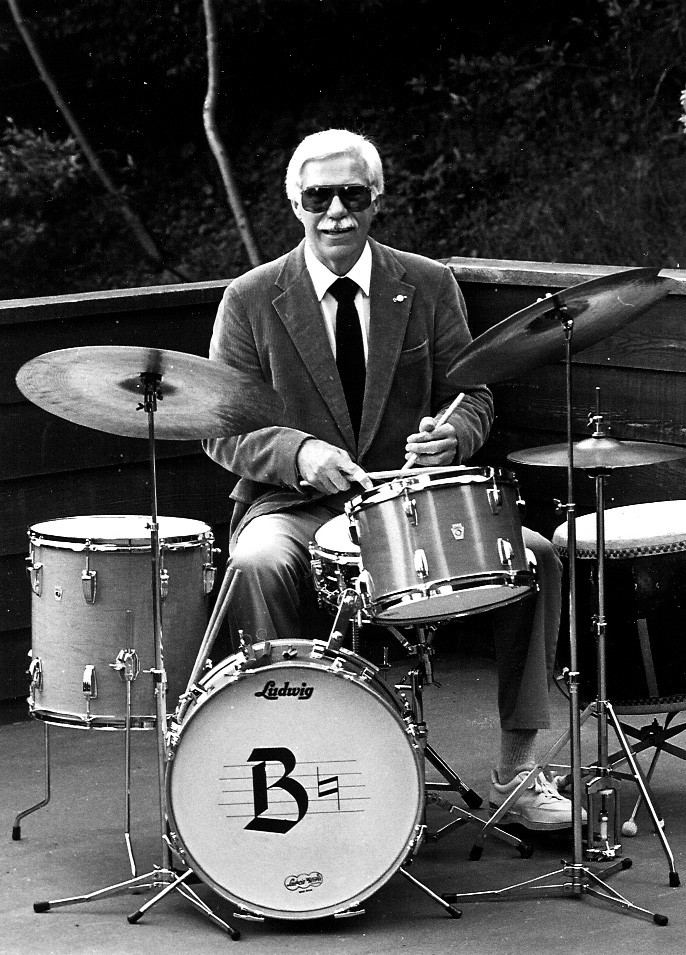

by Bob Jones

Benny Barth is a Local 6 jazz drummer who came up during the golden age of jazz. He was a founding member of The Mastersounds in the late fifties, and in the sixties played with Vince Guaraldi on the famous “Linus and Lucy” tune. As a casual musician, he played with many of the greats who came through the Bay Area, and is still active today. This article first appeared in The Jazz Times magazine in 1993, and has been edited for space. The full version can be found on the Local 6 website.

Benny Barth was born in 1929 in Indianapolis, IN, to Lucy and Jake Barth. As a child, Benny could be found beating on his mother’s pots and pans. He later took tap dancing lessons and also played the trumpet, but dropped it when he noticed the girls liked him better as a drummer. In 1941, his Uncle Ben Caldwell, for whom Benny was named, bought him a set of drums. In grade school he organized a band, and in high school, Benny was playing drums in the orchestra and concert band and practicing many hours a day.

Benny’s memories of his Indianapolis days are filled with the great players he listened to and played with in that Midwest jazz center. Among these were bassists Leroy Vinnegar and Max Hartstein, trombone players Slide Hampton and the Hampton Family Band, Jimmy Coe, Willy Baker, Jerry Coker and Pooky Johnson on tenor sax, the Montgomery brothers-Wes, Buddy, and Monk, Freddy Hubbard, John Bunch and Fred Williams-piano, Lee Katzman, Al Kiger and Conte Condoli-trumpet, pianists Jack Coker and Al Plank, and a number of Indianapolis drummers-Earl “Fox” Walker, Hal Grant, Charlie Mastropaolo, Sonny Johnson, and Dr. Willis Kirk, who later became president of San Francisco City College. Benny credits Indianapolis big-band leader Barton Rogers with teaching him to play the high hat on the second and fourth beat.

Sponsored by Willis Kirk, Benny became the only white member of the musical fraternity B. S. of I., the Bebop Society of Indianapolis. They presented local musicians in concert and gave scholarships to deserving students at the Arthur Jordan Conservatory of Music. Meetings were held every Sunday at members’ houses. “To open the meeting,” Benny says, “we would stand in a circle with our arms around each other and each one had to scat two choruses of Dizzy’s Oolya Koo. When the meeting was at our house and my parents saw that going on, why, they couldn’t believe it.”

During the last day job he held (at the RCA Victor record distributorship in Indianapolis in 1949), Benny needed to get off early one day because Buddy Rich was holding a clinic at Indiana Music Company, where Benny took his drum lessons. The clinic started at 4:30, but Benny couldn’t get off work until 5:00. By the time he got to the clinic, the place was jammed. His teacher, Buck Buchanan, motioned for him to come closer to the front, and Rich had to stop his presentation and wait for Benny to find a place. Rich looked at Buchanan and asked who this young fellow was. “That’s Benny Barth. He’s a bebop drummer,” Buchanan said. “Come in and sit down, Barth,” Buddy Rich said. “There’s room for bop here.”

The first drummers to impress Benny were connected with traveling big bands. Gene Krupa came through Indianapolis with Goodman, and Benny wanted to be just like him. But his friend, Lee Katzman, who cut high school and went on the road with one of the touring bands, told Benny to listen to drummers like Jo Jones, Big Sid Catlett, Dave Tough, and George Whetling. “As soon as I started listening to these drummers, I realized that there is so much more to playing music than I had thought. There is the feeling part. The drummer’s job is to make the whole band play. To kick it into gear. To do this, you have to have a feeling for what the music is about.”

So Max Roach, Kenny Clark, Roy Haynes, Philly Joe, and especially Art Blakey, became Benny’s models. When he thinks of the influence these players had upon him, Benny turns philosophical about his calling. “I realized that the drums are as much a musical instrument as the violin. I learned to tune my drums to the style of music being played. You do not need a massive array of drums and cymbals to be a jazz drummer. A high hat, a snare, a bass drum, a good twenty-inch cymbal are the basics.”

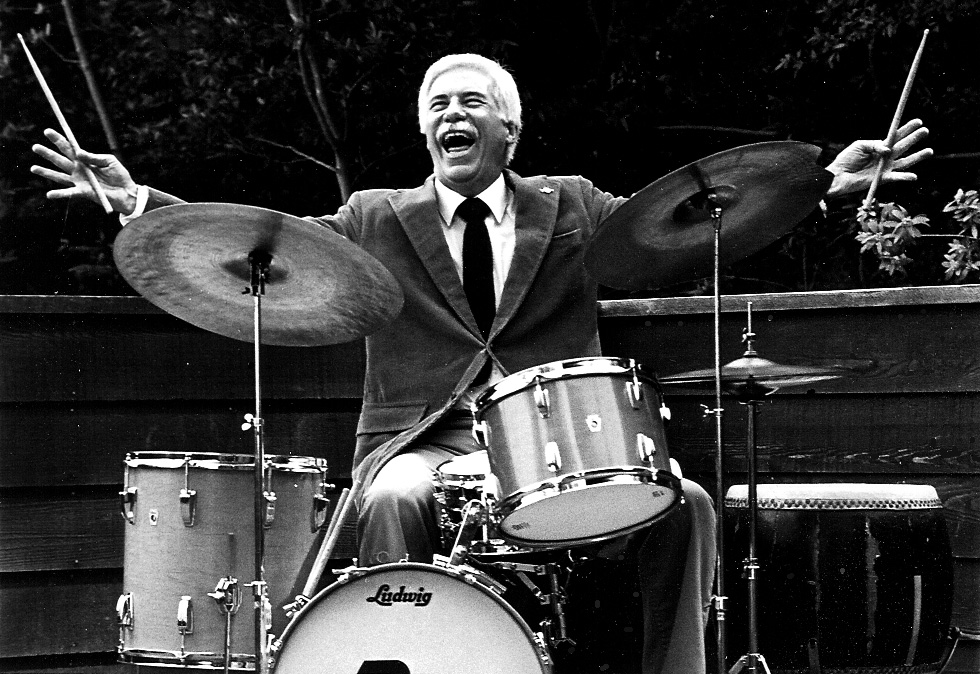

Warmed up to the intricacies of drumming, Benny goes on: “drums color the music, and in that sense, they are the most important instrument. You can get many different sounds out of just your snare drum. Drummers have their characteristic sound. Some say I sound something like Blakey or Max Roach. So be it. I don’t care. I don’t mind being mentioned with those two. But I think I have my own sound. It can take ten years or longer to find your own sound.”

Benny says his greatest musical memory was going on the road with the Montgomery brothers and forming the group called the Mastersounds. Buddy played vibes, Monk played electric bass (the first to do so in a jazz group, Benny says), and Richard Crabtree played piano. Wes Montgomery joined them on guitar for several recording sessions. “When the Mastersounds started out, we lived together in a big house in Seattle for several months in 1957, playing the Seattle clubs and traveling,” Benny says. “We rehearsed every day. It was full-time music.”

From mid-1957 to 1960, the Mastersounds’ home base was San Francisco. They appeared in local clubs and did gigs and festivals far and wide. “We worked real hard at it,” Benny says, “and our little unknown group from Indianapolis became recognized all around the country.”

The Mastersounds played the first Monterey Jazz Festival in 1958 and also the 1959 Newport Jazz Festival. They played the famous Blue Note in Chicago and the original Birdland in New York. During those years they did albums for World Pacific, both live and in studio. I asked Benny for his favorite recordings among these, and he named “Stranger in Paradise” from the Kismet album and a live cut from the Monterey Jazz Festival of “Un Poco Loco.”

When the Mastersounds broke up in 1960, Benny freelanced in the Bay Area, playing behind East Coast bands and the smaller groups that came through town. San Francisco jazz musicians worked six nights a week in those days, and maybe a Saturday or Sunday matinee. On Monday nights there were jams when everybody who happened to be in town got together at one of the clubs.

Benny remembers playing the great jazz clubs that were still going when he moved west—The Blackhawk, the Jazz Workshop, Sugarhill, El Matador, the Tropics on Geary, the Jazz Cellar in North Beach, Basin Street West, the Coffee Gallery, and there were others. One of his favorite Bay Area gigs was being part of the house rhythm section at the Jazz Workshop with Monte Budwig on bass and Vince Guaraldi on piano. Benny’s light tapping drumbeats can be heard on the famous “Linus and Lucy” tune that came out of that era.

Benny is happy to talk about being the drummer for Teddy Wilson when he came west. “Cal Tjader recommended me and Dean Reilly to Teddy,” Benny says, “and he picked us. I played brushes all night with Teddy on many gigs in the sixties and seventies. Helen Humes heard me with Teddy and Milt Hinton at one of the Concord Jazz Festivals and asked me to be in the group backing her. I backed some great singers after that—Irene Krall, Peggy Lee, Helen Forest, Joe Williams, Billy Eckstine, Sylvia Simms, David Allyn, and Jimmy Witherspoon.”

An especially high point in Benny’s memory is two weeks playing behind Jimmy Witherspoon and Ben Webster. “We did a lot of blues and a lot of Ellington, and we swung all night,” is the way Benny puts it. “The gig went from 9:00 to 1:30, including breaks, and when the night was over I always asked myself, ‘How could four hours go by so fast?’”

Many Bay Area jazz enthusiasts remember Benny Barth from the days as house band drummer at the hungry i with guitarist Eddie Duran. For several years, they played behind stars like Barbra Streisand, Mel Torme, and John Hendricks.

Benny’s long and pleasurable association with jazz guitarists, which began with Wes Montgomery, went on to include gigs with Joe Pass, Herb Ellis, Barney Kessel, Kenny Burrell, and Charlie Byrd. This continued in the Bay Area with recordings with George Barnes and the wonderful Ginza album on Concord Records with Eddie Duran and Dean Reilly. Barth’s drum playing is especially suited to the wide lyrical range and quickly changing feeling of the jazz guitar.

During these San Francisco years, Benny was married to his first wife, Janet, whom he met at Indiana University in the early fifties. They raised “two fine girls, Kim and Kendall,” in Benny’s own words. In 1987, he and Janet parted, and Benny moved to Guerneville, California, where he had made many friends from playing at the Russian River Jazz Festival in the formative years of that event. He married Diane Cosgrove in a swinging ceremony under the redwood trees that featured the seventeen-piece Rudy Salvini Big Band with maybe forty musicians sitting in from time to time.

Here along the Russian River, Benny has embarked on the third stage of his career. Among other local and Bay Area gigs, he plays regularly with the Bob Lucas trio with Tom Shader on bass. “I’ve played in the Lucas trio off and on for twenty years,” Benny said. “It’s one of my longest associations.”

Benny has been music director of the Cotati Jazz Festival and is drummer for a magnificent group called Bay Area Grand Masters that features Tee Carson on piano, Vernon Alley on bass, and Allen Smith on trumpet. He especially likes to play with guitarist Randy Vincent of Petaluma, and they get together often just to work out. With bassist Gary Digman, they formed the group Momentum, which has played the Cotati Festival and othcr gigs. Benny also returns to his hometown each May to play with the George Freije Big Band at the starting line of the Indianapolis 500 Speedway.

A couple of years ago, Benny had a new garage built, and over it he put a big room that serves as studio, storage for his drum collection, and a place for a pool table and several sets of golf clubs. Looking at the racks of drums along one wall of the studio, Benny says, ‘These are vintage jazz drums used in orchestras and little groups. Only two of them were made after 1960. No rock ‘n’ roll drums here.” This got him talking about his craft.

Benny on the cymbal: “A good ride cymbal will have all the tones of the diatonic scale in it. It will get better for maybe twelve years and then it might go dull and you have to find a new one.”

Benny on brushes: “God, I’d like to be able to find some good jazz brushes. I did a lot of brushes with the Mastersounds. They were light and flicky and felt good, but in time the strands would break off. After a gig I would see strands from my brushes on the floor. Now the brushes you can get are too stiff, and the sound isn’t as good.”

Benny on drumming in general: “This idea of bashing and pumping and playing loud all the time … there’s no reason for it. Good drummers can burn at a low flame. The idea is to play good music at any volume. I learned from listening to the other instruments. Listen to Gillespie, listen to Parker, Prez, and Jug. There is a range of feeling and tones. I also learned a lot from vocalists. Billie Holiday, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Peggy Lee. The tunes are trying to say something. I must know the lyrics to hundreds of tunes, and I think the lyrics when I play. And I love to shout some blues.”

Benny on the importance of drumming: “A good drummer can make a good band great. A good drummer can make a dull band sound good. If the drummer ain’t making it, no kind of band can swing.”

Some years ago, when he was still living in Daly City and had a weekend gig at the Flamingo Hotel in Santa Rosa, I came across Benny muttering to himself in the rest room. “They don’t pay us anything much, and we have to drive all this way, and we have to have these flashing lights from the ceiling, and nobody cares if we play good or not.. .” Here he wadded the paper towel he was drying his hands with and tossed it into the wastebasket for a perfect two-pointer. Then he continued “but they’re not going keep me from playing my drums.”

This, it seems to me, is the basic orientation of Benny’s ongoing life as a jazz drummer. You will still find him playing his drums every chance he gets. And when he’s not doing that, you will likely find him on the golf course at Northwood trying to hit his ball around a redwood tree.