Denny Zeitlin: “The Heart of the Matter.”

by Alex Walsh

“He is the jazz world’s most visible Renaissance man — a full time practicing psychiatrist, a medical school teacher, and a world class jazz musician.”

—Don Heckman, Los Angeles Times

Denny Zeitlin did not want a recording contract. He was in medical school and had to finish his degree. It was 1963. His friend, Paul Winter, an alto sax player with a contract at Columbia records, wanted to introduce Denny to his producer, John Hammond. Paul was sure John Hammond would love his playing, but Denny was reluctant. “I said, Paul, thank you, but no thanks. I don’t want to get involved in recording. I don’t want to have some A&R guy at some record company tell me what to play. I’m happy with what I’m doing.”

Denny Zeitlin did not want a recording contract. He was in medical school and had to finish his degree. It was 1963. His friend, Paul Winter, an alto sax player with a contract at Columbia records, wanted to introduce Denny to his producer, John Hammond. Paul was sure John Hammond would love his playing, but Denny was reluctant. “I said, Paul, thank you, but no thanks. I don’t want to get involved in recording. I don’t want to have some A&R guy at some record company tell me what to play. I’m happy with what I’m doing.”

Paul was persistent. He dragged Denny to the studio to meet the man who (unbeknownst to Denny) had discovered Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Charlie Christian, and Billie Holiday. “So I played a couple tunes for him. He was exuberant about my music and said, ‘Denny, I’d love to have you come on board at Columbia. You can record whatever you want. You can use whomever you want. No one’s going to tell you what to play.’”

“So I said, ‘Let’s do it.’”

Denny went on to record five albums with Columbia, all while completing his degree and establishing his career in psychiatry.

EARLY YEARS

Denny was born in Chicago in 1938. His father was a radiologist and his mother was a speech pathologist. They both loved music and both played the piano. “I have memories, from when I was two or three years old. I was sitting on my parents lap while they were playing, putting my little hands on theirs and going along for the ride kinesthetically.” When Denny began experimenting on his own, he says his parents very wisely protected him from premature formal piano study. “They just let me do my thing, and when I was seven I requested to start studying the piano.”

His interest in psychotherapy began when his uncle, a psychiatrist, started telling Denny about his work. Denny became fascinated with the idea of talking to patients and soon began counseling kids on the playground in 3rd grade. They would come up to him and talk about their problems, and he would listen and try to be helpful. “I had an idea very early on that I was going to be involved in these two fields in some way.”

Up until 8th grade, Denny had been studying classical music. But when his piano teacher played him a 10” Lp called You’re Hearing George Shearing, it changed his life. “I felt like I was shot out of a canon! Here is this amazing pianist who obviously has classical chops, but he’s playing this music that has all this drive to it and he’s making it up as he goes along. I said, ‘that’s what I want to do!’ And so from then on I just put all my energy into learning about jazz. And my folks were totally supportive.”

Denny started high school in 1952, and began forming his own combos. Being a tall kid, he was able to go to clubs with a fake ID and get musicians to show him what they were doing. “I would ask, ‘How did you voice that chord? How did you do this?’ There were no jazz schools in those days so the way you learned this art form was by osmosis and whatever informal apprenticeship you could set up. I did that all through high school and college.”

His early influences were all jazz pianists including George Shearing, Billy Taylor, Bud Powell, Lenny Tistrano, Horace Silver, Thelonious Monk, and Art Tatum. Some of the major Chicago clubs where he used to hang out and eventually sit in included the Sutherland Lounge, the Gate of Horn, the London House, the French Poodle, the Beehive, and the Streamliner.

Denny first heard Billy Taylor when he was 15 at the Streamliner on the west side of Chicago. “I loved his taste, humor, and the sophistication and exuberance of his music. He was very encouraging to me.”

Denny first heard Billy Taylor when he was 15 at the Streamliner on the west side of Chicago. “I loved his taste, humor, and the sophistication and exuberance of his music. He was very encouraging to me.”

One day Denny’s mother asked him to invite Billy Taylor and his trio to their house for dinner. “She said, ‘Denny, you like Billy Taylor so much, and he knows you’re a big fan, I bet his group would love to come to our house for dinner on a Sunday when they’re not playing. They are on the road and they might appreciate something like that.’ I was embarrassed and I said, ‘Mom, they’re not going to want to be with US!’ And she said, ‘Why don’t you just ask them?’ So I geared myself up and asked Billy if he would like to, and he said, ‘We’d love to!’ So Billy and his trio mates, Earl May, and Percy Brice, drove out to Highland Park from Chicago on a Sunday. I had my little fledgling jazz trio. We played for them and they played for us and we hung out and had dinner and it was just a tremendous thing. I still remember Billy telling me and my parents, ‘You know, Denny has a great talent for music, and I hope he always stays with music, but it’s a good thing that he loves medicine and that he’s going to be a doctor, because the life of an itinerant jazz musician is really pretty arduous. I know my wife primarily on the telephone.’ And that really resonated with me and it increased my resolve to do both of these things. So that was a very important influence.”

When Denny went to the University of Illinois in 1956, he found there were wonderful players in and around Champaign-Urbana, so he was able to keep growing as a musician while he focused on his studies. During these years he was able to jam with Wes Montgomery, Count Demon, Punchy Atkinson, Joe Farrell, Roger Kellaway and Jack McDuff. On weekends he would commute the 3.5 hours back to Chicago to jam in the clubs.

In 1960, Denny went to Johns Hopkins Medical School in Baltimore, MD. A few eyebrows were raised when his musical preoccupations became known to his professors, but he kept his grades and focus up, so it didn’t become a problem. After a night of studying, Denny says he would frequently sit in with Gary Bartz and his group at the North End Lounge in Baltimore.

KEEP DOING YOUR THING

After signing with Columbia, John Hammond suggested that Denny get his feet wet in the studio by being the featured pianist on a young flutist’s album that he was getting ready to produce. “Jeremy Steig’s debut–that was my first recording in 1963 on Columbia. Ben Riley and Ben Tucker and I were the rhythm section. It was a very exciting date.”

The album, Flute Fever, was met with good reviews, and Denny was now seen as an up and coming talent. During this period, he decided to call one of his favorite musicians, arranger and composer George Russell, to see if he could get a few lessons. “I called him up and said, ‘George, I’m here for 10 weeks on a psychiatric fellowship, is there any chance of getting some lessons from you? Your music has really inspired me.’ He said, ‘Sure, let’s get together and see.’ What emerged was interesting. Instead of me formally studying his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, we hung out together and I would play for him and he would point out things and mention things, and we would listen to records together. It was an invaluable kind of informal mentorship over 10 weeks. He was very, very, encouraging. So I count Billy Taylor, George Russell, and about half a year later, Bill Evans, as 3 pivotal influences in terms of this kind of encouragement and underwriting that a young artist can really use.”

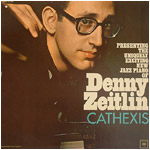

Denny’s first record, Cathexis, was also met with good reviews. After he recorded it he thought, “Why don’t I call Bill Evans? He’s in New York, maybe he’s willing to listen to this album and give me a few pointers?’ So I called him up. I’d felt emboldened to giving him a buzz because he’d been in a blindfold test a few months earlier where they had played a track from Flute Fever, and he said, ‘That piano player’s really great.’ So, I called him up and he invited me to his apartment. He was totally gracious. He said, ‘Denny, you know, my only suggestion to you is keep doing your thing. Don’t let anybody tell you what to play, man. You’ve got your own music, it’s special. Just do it.”

“Throughout the remaining fifteen or so years that I knew him before he died, he was always encouraging like that. Just respectful and excited about what I was doing.”

In 1963, Denny came out to San Francisco for a summer psychiatric fellowship at UCSF, and fell in love with The City. He decided to return the following year for his internship and residency at UCSF. He was still under contract with Colombia and began to think of how he could put a trio together.

He found out that bassist Charlie Haden was living in San Francisco, so he contacted him and they hit it off. “I’d first heard him on albums with Ornette Coleman and he knocked me out. It turned out he’d heard my Cathexis album and really loved it so we got together and started looking for a drummer. I found a marvelous drummer, Jerry Granelli, and the three of us worked together for several years. We made two and a half albums together for Columbia.”

Denny had a standing Monday night gig at the Trident in Sausalito for three years. If he was supposed to be on call at SF General on a Monday night he would get one of his colleagues to cover for him and he would reciprocate. “I was able to keep that Monday night sacrosanct, and then I would do other gigs. We played some stuff in Los Angeles and up and down the coast, and the Newport and Monterey Jazz Festivals. It was great playing with those guys, it was a great trio.” Denny’s work was garnering international acclaim, reflected in two first place awards in the Downbeat International Jazz Critics Poll.

They recorded the album Carnival in Los Angeles, and the album Live at the Trident at the Trident. Denny’s final project for Columbia, Zeitgeist, was recorded with two different trios, the second including Oliver Johnson on drums and Joe Halpin on bass.

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS

“Denny? Philip Kaufman here. You may know my movies. I’m doing a very interesting science horror film and I’d love to talk with you about doing the music…”

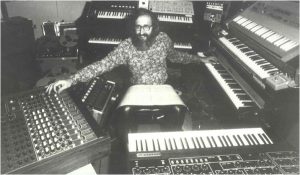

After his Columbia contract ended in 1967, Denny withdrew from public performance for a few years to develop a pioneering approach to multi-genre electro-acoustic music.

“I had engineers build me equipment because back then you couldn’t go into your corner grocery and come out with a synthesizer under your arm. I ended up with a rig that looked like a 747 cockpit. It would take 6 hours to tear it down from my studio, bring it to the gig, set it up, play the gig, and another 6 hrs to undo all of that. I did that for a decade. I was really committed to this music.”

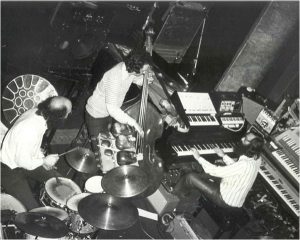

During the 1970s, Denny released two albums of electro-acoustic music for 1750 Arch Records, Expansion and Syzygy, and composed and performed the Jazzy Spies music for Sesame Street. His main musicians during these years were George Marsh on drums and either Mel Graves or Ratso Harris on bass.

In 1977, Denny got a call out of the blue from film director Philip Kaufman asking if Denny would score his next picture, a remake of Invasion Of The Body Snatchers. Philip Kaufman had grown up in Chicago, had heard Denny’s music, liked his records, and had it in his head that one day he’d like him to do the score for one of his films. Denny was floored. He agreed to take on the challenge which led to 10 weeks of twenty hour work days. “It brought to bear everything I’d ever been involved with in music, plus a number of new challenges.”

Denny wrote for symphony orchestra, which he had never done before, as well as for small groups. He went to Hollywood to record the orchestra and brought the tapes back to his home studio to overdub electronic elements. Sometimes his demos became the final cues in the movie. “I played Kaufman a demo of each cue before I would then go into several days of scoring, collaborating with my orchestrator, and recording. It was exhilarating and challenging, but it was exhausting because I also knew at any moment I could be fired. Because that’s what happens in Hollywood. Sometimes they have 2 or 3 composers before a score gets finished.”

Invasion Of The Body Snatchers was a big hit. It got very good reviews and the music got good reviews. Soon Denny started fielding calls from producers and directors asking him to score their pictures, but he turned them all down.

“I figured I’d lucked into this situation. I’d had the best of all worlds because Philip Kaufman gave me carte blanche to do whatever was needed. I had the best musicians in Los Angeles, the best scoring stage, the best engineer, the best orchestrator, the best conductor– it was first class. I could do another 100 films before I’d have something like that again. So I said, ‘Quit while I’m ahead. I had a good taste of this, stay with the filet mignon.’ And for me that’s been the big challenge – what’s the filet mignon of music, and of psychiatry?

A QUESTION OF BALANCE

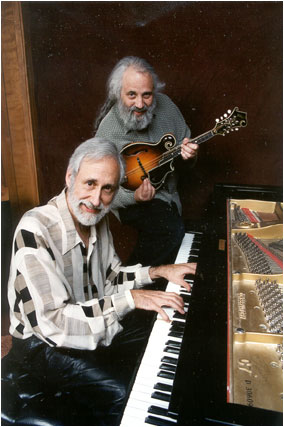

Denny returned to the acoustic piano and throughout the 80s and 90s released critically acclaimed albums on various labels including ECM, Windham Hill Jazz, and Concord. He played festivals internationally, choice club dates, and college concerts, as well as appearing on late night national TV shows. He concertized with many of the jazz greats including Joe Henderson, Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny, Tony Williams, Bobby Hutcherson, John Patitucci, John Abercrombie, Marian McPartland, Charlie Haden, David Grisman, Kronos Quartet, Paul Winter, David Friesen, Matt Wilson, Buster Williams and many others.

“Doing both music and psychiatry, there’s no way I can do each of them with the intensity I could do either one of them if I were doing it utterly full time. I always sensed it’s going to involve some compromises. But I can do that if I find out what’s really the heart of the matter in each field for me, and honor that, and be careful not to get seduced into other areas of either field that don’t really fit.”

In the 2000’s, Denny delved back into electro-acoustic music. He released several albums in that genre, and has a new one, Riding The Moment, with drummer George Marsh, coming out this year. Today, at 77, Denny is happy to play a few concerts a year.

“Doing another film score doesn’t really fit for me. Going out on the road for six months of the year doesn’t fit with me. I’ve got patients that I feel responsible for on an ongoing basis. I have teaching and supervisory responsibilities at UCSF where I’m a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry. I have a life with my wife Josephine. We’ve been together since 1967, and I treasure that as the hub of everything I do. I don’t want to be away from her for weeks and weeks. And I have other things I’m passionate about: fly fishing, running, collecting wine, and celebrating Josephine’s incredible cooking. With my musical time I want to be playing and growing. I want to be composing and improvising. I want to keep developing my studio and learning more about the galactic possibilities of sound, and paint with those colors. That’s the heart of the matter of music for me.”

“By any measure, Zeitlin’s output over the past 50 years places him at Jazz’s creative zenith.”

— Andrew Gilbert, JazzTimes

For more information about Denny visit www.dennyzeitlin.com